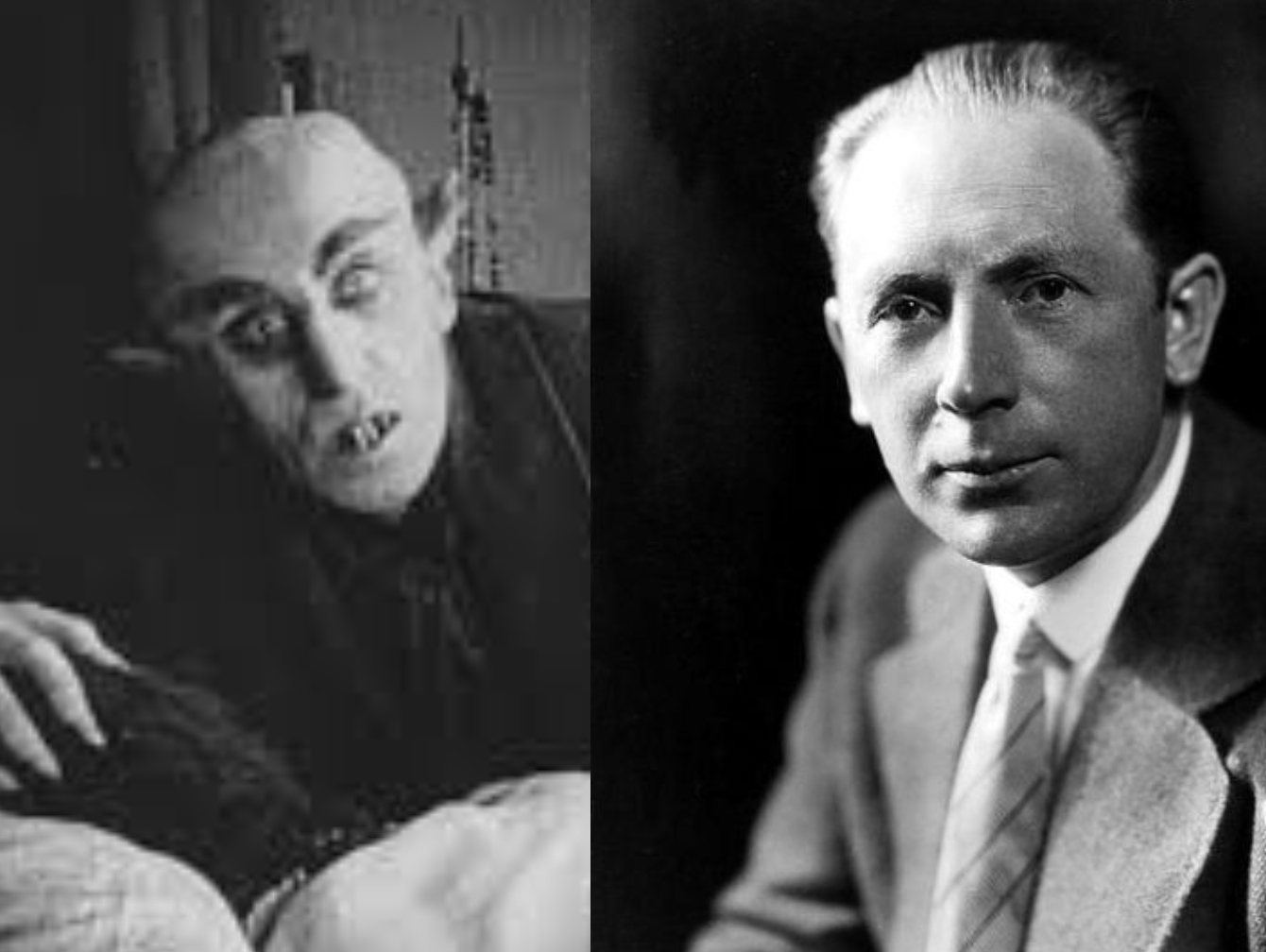

Nazi officers wore hats emblazoned with a big skull right in the center, and yet it never occurred to them It’s hard to believe that the Nazi officers who wore hats emblazoned with a big skull on the front never questioned whether they might be on the wrong side of history. One possible contributor to their lack of insight might have been their rarely if ever having to see themselves with the hat on. Perhaps in the morning when they got dressed but not while they were performing their duties. Had there been cellphone cameras and videos back in 1938 maybe things would have been different. Candid images of them in the course of their duties might have made their way back to them. There would be no monopoly of vision. The points of view of the perpetrator and the victim would exist side by side.

Joseph Goebbels himself recognized the importance of controlling the public narrative. He explained that The Third Reich never could have risen to power without the radio reaching into everyone’s home. He developed a principle for his propaganda, “one transmitter, ten thousand receivers.” Long before Marshall McLuhan, Goebbels understood the power dynamics of mass media and the need to control it.

We’ve all seen footage of people waving their hands in an attempt to stop a cameraperson from filming them. For some people, it seems almost like an instinct. The question is why? Why does a policeman or soldier shove his palm in front of the lens?

The common assumption is that they know what they are doing is wrong, but it’s unlikely that it is that simple. There are multiple possibilities at play but at the core of it is an undeniable power dynamic. One person is doing the shooting and the other person is being shot. The language makes it clear. Even if you are engaged in laudable endeavors being shot feels like being judged. All of a sudden there is a spotlight on you and you have lost control of how you are seen.

This immediate reaction to becoming the subject is only the first step. Next, the person being filmed will inevitably become self-conscious. The term self-conscious is a powerful descriptor. It doesn’t just mean a state of self-awareness it carries with it a feeling of discomfort and even dissociation as if our natural state is one in which we are not self-conscious. We are more comfortable looking at and evaluating others than we are looking at and evaluating ourselves. We prefer a state of self-unconsciousness.

The SS Officer may have an inkling that what is happening around him is wrong but he may not feel as though he is truly involved in it. He doesn’t see himself doing anything and so can minimize his role. His reaching out to stop a camera might be an instinctive need to protect his own ignorance, his own denial.

When Jean-Paul Sartre famously said that “hell is other people” he was not complaining about how annoying everyone was, even if he did live in France, the Mecca for annoying people. He was referring to our having to see ourselves through other people’s eyes. We instinctually do not want to see ourselves because we do not want to face our actions. You don’t have to admit that you watch porn until someone accidentally stumbles across your browser history. Now you must come to terms with the idea that you are a masturbating porn consumer, something you could hide not only from the world but from yourself as long as you went unseen and un-judged.

Documentary filmmakers often find themselves in a position of having to comfort their nervous subjects and downplay the intrinsic power dynamic of their being filmed. Even the word “subject” carries a message about submission. The subject of a film is the central character, they are what the film is about, but the word “subject” can also mean inflict. You are being subjected to scrutiny. These two meanings overlap. As the one in front of the camera, you are the topic of interest, the thing to be seen and evaluated. The intentions of the person behind the camera hardly matter. Either way, you are subjected to being the subject.

If you are the subject it doesn’t matter if the documenter’s intentions are favorable or not, either way you have lost control of how you are seen. They can edit you, recontextualize you, or even use trickery to make you look like you did or said something you haven’t.

The person behind the camera, and through them, the audience, are labeled observers. Observer and objective come from the same root. We, the observer, believe we have access to objective reality. We trust what we see, but what we see on film is not reality nor the whole truth. In this way, the subject who protests against being filmed may not be hiding the truth but instead protecting it. The subject may feel an obligation to protect what they are doing from a kind of scrutiny that may misunderstand or misinterpret what is being recorded.

Film can never tell the whole story. It can only capture the camera’s point of view. What it captures is the light reflecting off what the camera person has pointed it at. That light is subject to blur, reflections, refractions, overexposure, underexposure, and a hundred other distortions. Then there is the frame rate to consider, and its position in relation to what it is filming.

In the end, all film is essentially a lie. It is an illusion caused by the persistence of vision. We are not seeing reality, we are seeing thousands of little two-dimensional images that the camera person decides to show us. The illusion is compounded by the apparent absence of the camera person. When we sit and watch the screen there is nothing physically between us and what we see, but in truth, there is a camera person who is actually our invisible intercessor, our unseen mediator. The fact that they are unseen allows us to forget them. It’s as if we are transported to the scene without a vehicle of any kind.

Again on an instinctual level the subject being filmed knows that the person filming them is the unseen mediator. The person holding the camera will not be considered in the end, only the subject. The audience itself will be invisible. As the images move on the screen the audience loses track of their status as the observer. In fact, this illusion is at the heart of film. We can be frightened or aroused or made to feel anything by dissolving the observer/observed dynamic. We end up believing we are there. We may duck in our seats, or scream out. Our status as observers is forgotten.

Those people trying to prevent themselves from being filmed do not have to think through this whole academic deconstruction to know that one end of the camera has an advantage over the other. There is a powerful connection between seeing through someone’s point of view and adopting their metaphorical point of view. To see through someone’s eyes is to literally gain sympathy with them, not necessarily “for” them but “with” them. You adopt their physical point of view which lays the groundwork for adopting their mental point of view.

The camera is a limited and imperfect conveyor of reality. We ourselves are imperfect receivers of reality. Reality is a hypothetical concept and is malleable by nature. We all know that reality is elusive and we constantly struggle against each other to define it. Just as two gunslingers in a western might fight over a gun in the dust to see who will get to be on the wrong end, so too we intuitively know that the finger on the record button is the finger on the trigger.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/there-has-never-been-a-film-like-the-act-of-killing

[…] If this interested you, you might also be interested in this - www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/whose-side-of-the-camera-are-you-on […]

[…] If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/whose-side-of-the-camera-are-you-on/ […]