Fiction and non-fiction films are often separated into mutually exclusive categories, but the boundaries between the two are not so clear. When you see Ryan Gosling kiss Rachel McAdams in the fiction film The Notebook, the story may be fictional, but the kiss is real. The camera is documenting a real event. Conversely, in many documentaries, the subjects know they are being filmed, which prevents them from acting “naturally.” They will, to more or less of an extent, perform like an actor for the camera.

Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams had serious problems getting along during the filming of The Notebook. In many reports, they were said to have actively hated each other. How does this change the "documentary aspects" of the kiss? The kiss really did happen, but it represents an event that was staged. In the two images above, the one on the right is a still from The Notebook. It is an illusion created by two people kissing, but not for the reasons people normally kiss. The image on the left is a photograph taken at the MTV Movie Awards and presents the same kiss, but with the assumption that it is “real,” meaning that it is the result of genuine affection. They were in front of a camera in both images and were performing in both images. Are both kisses fake? If someone asked Rachel McAdams what it was like to kiss Ryan Gosling, should she qualify her answer, or can she say she knows what it was like?

The fact that the two actors disliked each other was a juicy bit of gossip that people enjoyed precisely because it contradicts the perceived “reality” of what was seen on screen. The fact that they were acting is not surprising, but the fact that they had to kiss and look lovingly into each other's eyes is surprising because the line between reality and fiction has been blurred.

Is Jackie Chan really fighting bad guys in his films? The guys are not “bad guys” per se, and they are not trying to hurt Jackie, even though they almost always do. However, one of the reasons we go to a Jackie Chan movie is to marvel at his acrobatic prowess and martial arts skill. What he does on screen requires real discipline and dedication, because he is really doing it. Yes, it is choreographed. Yes, it is many separate shots mounted into an impressive, inhumanly long montage, with breakaway chairs and bottles made of sugar, but still, what you see is really happening. If Jackie Chan didn’t know kung fu, we wouldn’t appreciate his films the same way, or perhaps at all. Jaden Smith had to really train in real kung fu to star in The Karate Kid.

This may all seem like academic semantics, but when you apply it to pornography, it’s even more difficult. Are pornographic films documentaries? Many porn actors and actresses have significant others and separate their job from their personal life. Separating intercourse for work and intercourse for affection is delineating a difference. Would you be jealous if you were the non-porn actor at home, waiting for your spouse to return from a day at work?

What is happening on the screen when two porn actors engage in intercourse? Using some kind of romantic distinction like they’re not being in love doesn't work. Lots of people have sex with people they don’t love, or with strangers, or with friends, and some porn actors have deep feelings for their on-screen partners.

What exactly are the couple in the photo below doing? It doesn’t seem possible that both of them are solely thinking about their paychecks. It is possible that they aren’t enjoying themselves, but their bodies have to react to stimulation, even if their thoughts are negative. If she feigns enjoyment or fakes an orgasm, that too can happen off-screen as well.

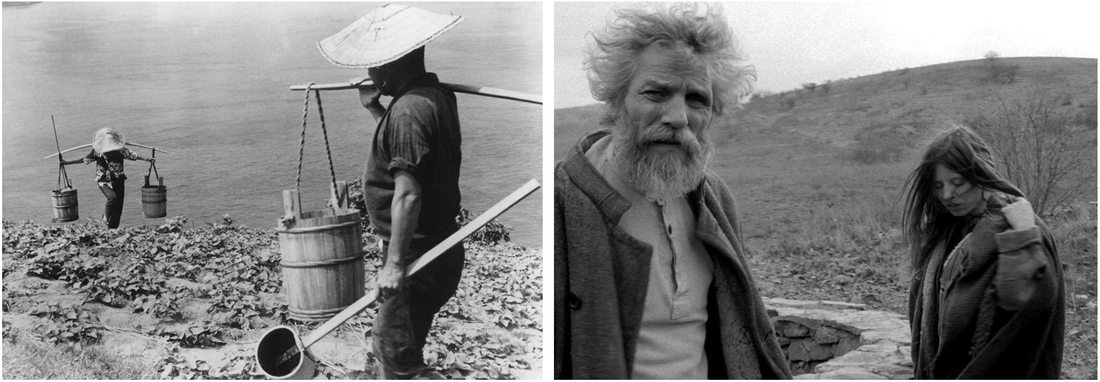

Just as fiction films are not entirely fiction, documentaries are not entirely real. When Ken Burns interviews Shelby Foote for Burn’s Civil War documentary, Foote may not be working from a script, but he certainly prepared for the interview, and you can be sure Burns edited out slips of the tongue, or dead moments. Foote is not “being himself”, he is projecting a self-conscious version of himself as a professor, historian, and intellectual, complete with beard and pipe. Of course, he also does this off-screen.

Anyone with a camera in their face immediately becomes acutely self-conscious, in the most literal sense of the word. We become painfully aware of our own appearance and behavior, making it very difficult for us to act “naturally.” We keep thinking about what the camera sees, and about the unknown mass of people who will see the film. A camera is a bit like the electron in Heisenberg’s experiment. You can not observe something without changing it.

Some documentaries take special pains to minimize or hide the presence of the camera from the subject. This may eliminate some of the problems, but there are still aspects of artifice at work. No matter how spontaneous, uncontrolled, and unedited film footage is, it still only represents a single point of view from a single period of time. Reality cannot be captured by a camera or a two-dimensional image projected onto a screen. Reality doesn’t have a story arc, or even a beginning and an end. Documentaries are constructed stories that string events into meaningful patterns. They are stories, and even if they are based on true events, those events are curated, edited, shaped, and strung together to create something not so dissimilar from a fictional story.

This essay is intended to blur the line between documentary and fiction, but not to erase it. There are still facts that documentaries can convey, and although their relationship to reality may vary, documentaries are still an important mode of information dissemination. All films disseminate information, fictional or otherwise. All films mediate our experience of something that happened at another time and place. Sometimes it is the fictional worlds that we find the most compelling. We are genuinely frightened by a horror film because we cannot stop ourselves from suspending disbelief. After the movie, when you decide to sleep with the light on, you are confusing fiction and reality. You can tell yourself, “It isn’t real”, but that seldom alleviates the fear.

Just as fiction can seem real, there are documentaries that don’t seem real. How can anyone absorb the scale of the Holocaust? It all seems like a nightmare that happened in another time and place. If we watched Shoah and truly understood the reality of what we were seeing, it would brutally traumatize us, leaving us permanently damaged. We have to use some measure of dissociation to be able to survive watching it. You can believe it is true without fully acknowledging to yourself the gravity of what you are seeing.

I don’t know if this is a measure of anything, but which is more likely to give you nightmares, a fictional horror movie about a serial killer or a documentary about a serial killer? The answer has something to do with our objective, rational absorption of images, and our subjective, emotional response to images. The kiss in The Notebook is staged, but we respond emotionally because, as part of a story, we believe in it. It doesn’t matter whether it is true or false, the story and the kiss make us respond as if they are real.

Regardless of what has been said so far in this essay, the fact remains that there really were millions of people who died horribly at the hands of the Nazis. Jeffrey Dahmer was a real person, and his victims really did suffer and die. No amount of academic analysis will change that. It is only how these events are documented and the way we respond to it that is being questioned. All documentaries necessarily fall short of the truth. Even the idea that there is one, singular, definitive truth is a problem in and of itself, but that does not mean that documentaries are useless, and it does not mean that documentaries do not capture some aspect of the truth. We would do well to remember how illusive truth and reality can be.

Epilogue

After finishing this article, I was scrolling through one of those addictive YouTube Shorts collections when a clip from what must have been a Notebook press junket appeared. To my amazement, a child in the audience stood up and asked Ryan Gosling precisely what I was writing this article about, “In the scene where you were kissing the girl, was that real?” Everyone laughed and then Ryan tried to answer, ”I guess it was kinda real, but um… How do I answer this? This is being broadcast everywhere, too? Um, I didn’t mean it? This is the thing. I don’t know how to explain this to my own kids, but they watch this and say, like, 'Daddy, what are you doing?’ Like, it’s like exactly the tactic I would use on them. Not anger, but just disappointment.”

Gosling himself doesn’t understand what he was doing. It is also interesting that he points out how difficult it is to think while on camera. He wants to answer, but he is changing his words because he knows he is being filmed.

The most basic attraction of film is its similarity to reality, be it fiction or non-fiction. It is thrilling to see photographs move, because photographs are seen as direct representations of reality. If we didn’t believe this, movies would be no more interesting than cartoons. When Batman leaps out of the cartoon world and into the “real” world, we are thrilled by the perceived transformation. We enjoy the fantasy of reality.

If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/whose-side-of-the-camera-are-you-on/