Before he made Tommy (1975), Altered States (1980), Gothic (1986), or The Lair of the White Worm (1988), Ken Russell made The Devils (1971). It predates Greenaway but the lush and baroque nature of The Devils feels very much like something Greenaway might make, until Russell goes hurtling over the top, as he is apt to do.

The Devils is more ambitious than Russell’s later films. It is broader and looser with its imagery, leaving open different possible meanings and associations. Russell takes on an actual historical event from 17th century France but embellishes it with graphic splashes of blood, sex, and hallucinations. It is essentially the story of the rise and fall of Urbain Grandier, a priest who was accused of witchcraft and then burned. To his credit, Russell doesn’t seem to lionize or demonize Grandier, at least for the majority of the film. In the end, Russell ends up allowing Granier a few self-righteous soliloquies.

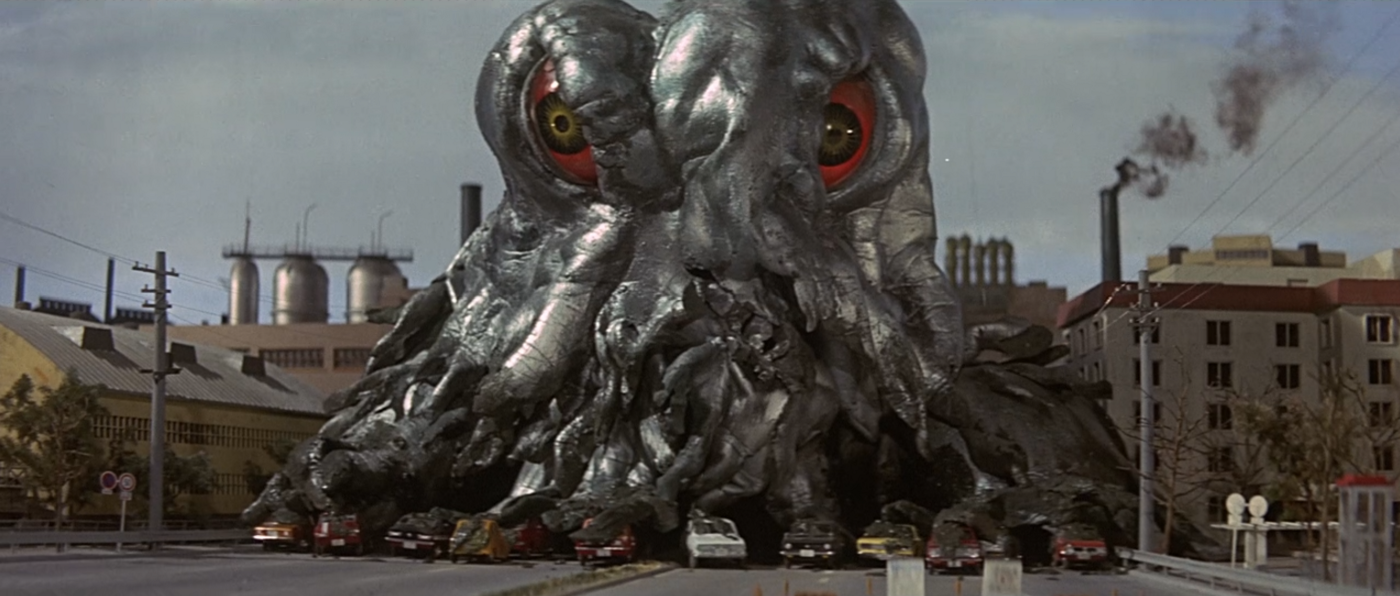

Beyond the specific story of Grandier, The Devils is a period piece about a plague-ravaged and desperate France. Louis XIII, demented by power and money, rules from his sequestered fantasy world on high. He oversees a decadent court obsessed with opulence and marked by a pathological fear of Protestants.

The film is partly based on Aldous Huxley’s book, Devils of Loudun (1952) which covers the same events. The witch burnings in Loudon, like the witch burnings in Salem, provide fertile ground for critiquing societal beliefs. Foucault’s Discipline and Punish came out 4 years after Russell’s The Devils but they certainly make a close pairing. Russell definitely saw the same connections between the body and the state. The Devils is intensely corporal, mixing pain and pleasure, sex and death, the body and the spirit into a chaotic spectacle.

Even though the plot of The Devils is restricted by history and by a source text, it is one of Russell’s most adventurous and outlandish films. The story is specific, but the themes of power and avarice are right up front permeating everything. There isn’t a moment of the film that isn’t focused on the struggle to either dominate or deceive.

Focusing on the nature of power and lust furthers the film’s sympathies with Greenaway. Both directors pile on the corporal and fecund imagery of bodies, food, costumes, and symbols like some deranged Dutch master’s still life. Many of Russell’s films involve bursts of symbolism, especially flashes of the crucifixion, but The Devils dives deep inside the imagery. In films like Altered States, the images jump out like Jungian dreams across the screen, but in The Devils, the characters actually inhabit the rich and chaotic world of fever dreams and hallucinations.

Beyond Greenaway, there are also direct references to Bergman’s Seventh Seal. Near the beginning of The Devils, Russell uses Erik Nordgren’s lachrymose in the soundtrack. The lachrymose is the sinister prayer sung in The Seventh Seal when the procession of self-flagellating penitents enter the village. There are also numerous references to The Seventh Seal’s iron grate that separates the sacred from the profane. The Seventh Seal’s protagonist, Antonius Blok, continually finds himself locked out of the spiritual world with his face pressed against the bars as he pleads to be let in. Throughout The Devils, iron gates and bars function similarly.

Still, The Devils is considerably different from The Seventh Seal. Bergman’s film depicts a genuine and earnest struggle with faith and meaning. Russell’s characters are far too Machiavellian to care about anything other than terrestrial matters. Their religious fervor is a show to distract from their avarice, save perhaps for Grandier who sometimes seems genuinely conflicted. The title “The Devils” is plural because the movie is not concerned with the singular biblical Satan, but instead focuses its attention on the devil-like behavior of the all-too-human characters that populate the film.

The release of The Devils in 1971 was greeted with vitriol and condemnation. Ebert gave it zero stars. Even after being censored, it was still given an X rating. Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote in his review that the film was "not anti-clerical—there's hardly enough clericalism to be anti anymore—it is anti-humanity.” Which is a fair evaluation. He meant it as a criticism, but it could just as easily be taken as simply an accurate understanding of what Russell was after. Oliver Reed, who starred in the film, commented: "We never set out to make a pretty Christian film. Charlton Heston made enough of those... The film is about twisted people.”

The Devils is not a perfect film, but it is one of Russel’s best. Russell had and has a tendency to stumble into melodrama. Perhaps the fact that Russell made The Devils early in his career allowed him to be a bit more adventurous. He may have benefitted from not having fully fleshed out a style or approach to filmmaking yet.

The Devils does not fit easily into a genre or label. It’s a storm of ideas and images that requires some fortitude to face. One such image that was too much for censors to bear was during the final moments of the film when we see the mentally unstable Mother Superior masturbating with the remains of Grandier’s burnt femur. It is a potent and disturbing image that brings all the themes of the film together. She had been obsessed with Grandier and her lust for what she could not have, drove her to destroy him. She becomes a final vector of not only the sacred and the profane, but of perversion fueled by power and seclusion.

The fact that Russell’s film was censored and maligned could be seen as a recapitulation of its themes. The film was labeled sacrilegious and obscene and shunned just as Grandier was shunned. There is a line between the depiction of a third-person narrative and a first-person depiction of personally held beliefs, but in The Devils, the line can be hard to discern. In presenting obscene material, is Russell himself being obscene, or is he referring to obscenity in the third person? I think an argument could be made that he is doing both. Russell clearly intends to shock his audience, but part of the shock is perhaps based in our own attraction to some of the forbidden imagery. Our outrage is part of our appreciation of the film and points to its continued relevance.

If you enjoyed this you might also enjoy - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/jan-svankmajers-conspiracy-of-pleasure/