I was first introduced to Bill Plympton in the mid-1980s when, as an adolescent, I sat in front of the newly founded MTV, greedily absorbing all that it flashed in front of my pop-addled eyes. Between the music videos from Pat Benatar, The Go Gos, and The Human League, MTV played a few of Plympton’s shorts like Your Face. I remember thinking Plympton’s sketchy style looked messy and unfinished. His cartoons were more irreverent and weird than the usual stuff on regular TV like He-Man or Voltron. Plympton’s characters exploded, imploded, juggled body parts, and ate themselves. It was all pretty unusual.

Plympton’s full-length feature film Mutant Aliens was released almost two decades later in 2001, but the same irreverence was still evident. Mutant Aliens, along with Hair High (2004), were parodies of genre films. Hair High was modeled after a 1950s-style tough-guy greaser movie, and Mutant Aliens set its sights on sci-fi.

The plot of Mutant Aliens is a bit more circuitous than your average sci-fi fare, but it’s not the plot that makes the movie. Plympton is clearly more interested in the drawings and the animation than he is in making a coherent narrative. Usually animated films are constructed as a means of illustrating a story. Plympton tends to reverse this hierarchy, making the drawing and its movement the focus. He obviously relishes drawing and manipulating imagery. He is adept at simulating wide-angle distortions and fluidly morphing images into grotesquely proportioned caricatures.

Mutant Aliens may have been made in 2001, but Plympton's sensibilities were still thoroughly 80s. He had a counter-culture bent that recalls films like Society or Class of 1999. Movies from the 80s focused on corporate greed and government corruption, whereas Plympton's counter-culture forebearers like Ralph Bakshi or Robert Crumb focused on sex, drugs, and alienation. The 70s zeitgeist had been marked by bitterness and anger. People were still dealing with the collapse of the creativity and optimism of the 60s. The 80s were what came after the 70s mourning process was over. Culture coalesced into something more cynical and detached. The 80s preferred satire over parody. Capitalism felt inescapable. It had won, and now all that was left to do was indulge in it. Plympton’s 1985 short Boomtown looks like a promotional video for the arms industry. Two curvy women with enormous, unmoving smiles enumerate all the benefits of government defense spending. There’s no resolution or moral at the end, only gleeful celebration of the military-industrial complex.

Mutant Aliens follows in the same vein. The film is about astronaut Earl Jensen and his daughter Josie. Recalling Ripley's mission in Alien, Jenson's mission is undermined by corporate greed and he ends up marooned in space. Much of the film is seen through Jenson's flashbacks, but Jenson turns out to be an unreliable narrator, which gives Plympton all the room he needs to set his gonzo animation style free.

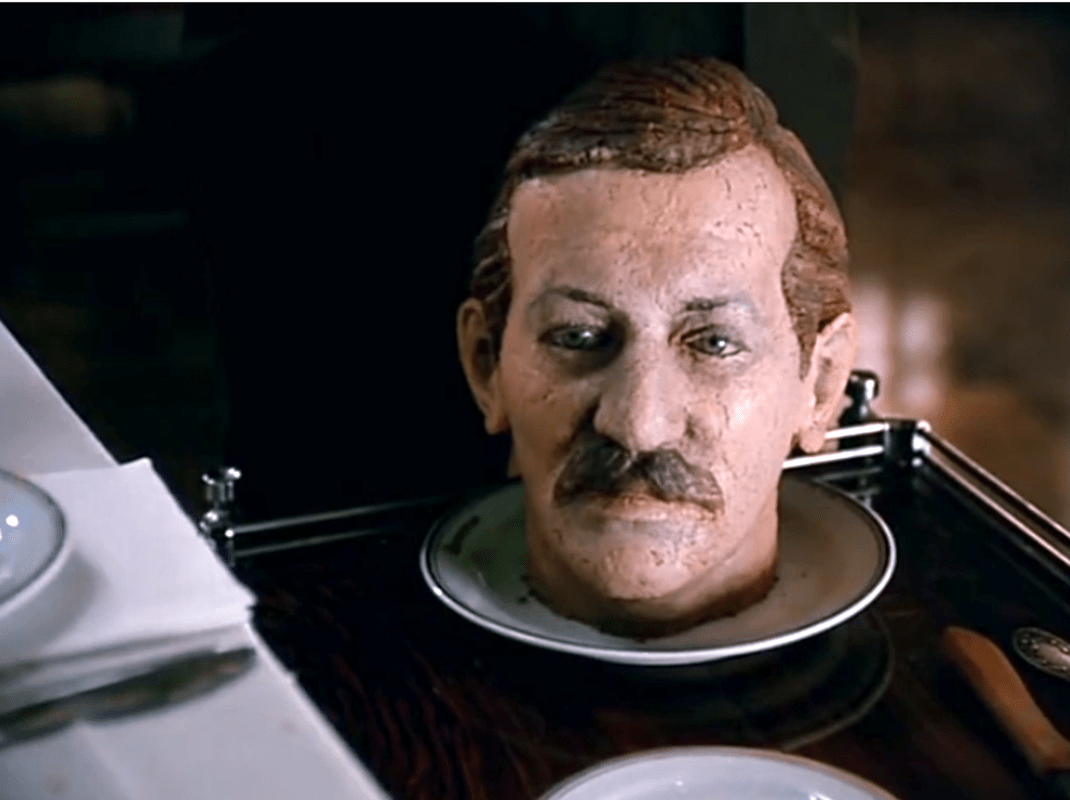

Plympton's characters all seem to be made of rubber. Characters often scrunch up or fly around like a rapidly deflating balloon. They smoosh, ricochet, and often break into bloody chunks of flying goo. His films have nudity, sex, and gore, but they are less graphic than they are goofy and ridiculous.

He has a way with sequences and timing. His scenes are full of edits that mix close-ups, cut-aways, and different angles into a series of exaggerated slapstick gestures and associations. Plympton mimics the in-your-face style of television commercials and the obnoxious, smiling stupidity of nightly news anchors. The way he throws his imagery at you is a parody in itself. He could present you with an ordinary object like an apple, but by placing it in the hands of a grimacing salesman seen through a fisheye lens, the whole thing takes on the absurd feeling of ridicule.

If you keep an eye out for him, Plympton pops up everywhere. He’s made music videos for Kanye West and "Weird" Al Yankovic. He drew a whole bunch of couch intros for The Simpsons. He had a recurring comic strip in The SoHo Weekly News. His animations have been at Cannes and Sundance. Recently, he made a series of satirical pieces using sound bites from Trump speeches.

Plympton continues to satirize and parody American culture while simultaneously participating in it. You might not be surprised that he worked with "Weird" Al or Matt Groening, but he also made a slew of commercials for companies like Geico, Microsoft, and AT&T. He turned down Disney when they asked him to work on Aladdin, but he made animations for the History Channel. It’s hard to predict his choices, but that is certainly part of what makes him such an interesting animator.

If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy this - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/cartoonish-depictions-in-a-cartoon-the-controversy-over-mutafukaz/