“His genius was in his way of looking at things, at singling out common objects for extraordinary examination. But the idea of looking at a Campbell's soup can as a work of art is what's interesting: the idea, not the can.”

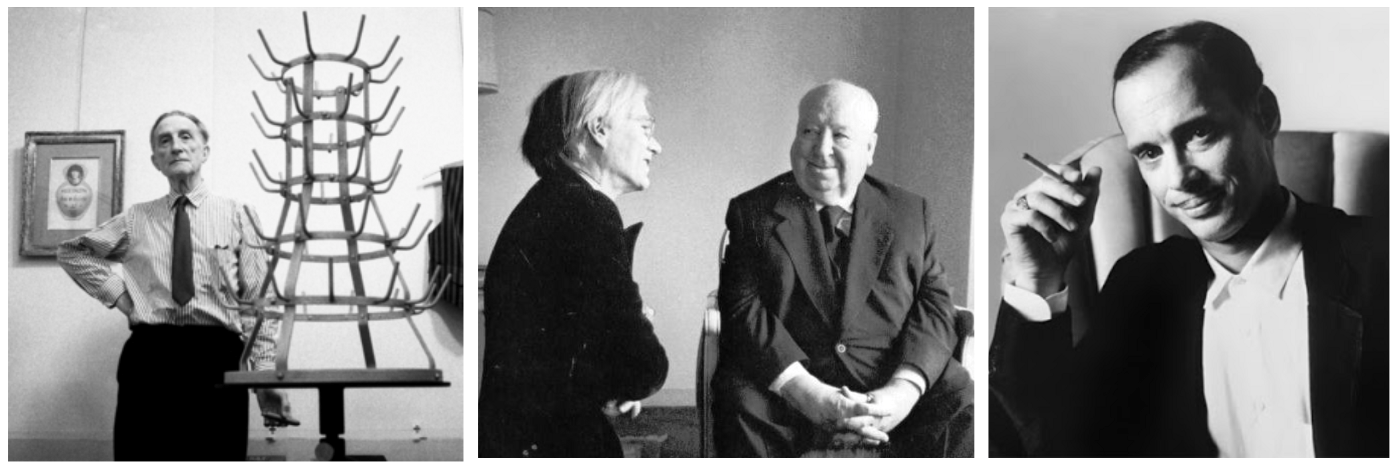

This excerpt is from Roger Ebert’s review of Andy Warhol’s 1968 film Flesh. Ebert is referring to the film, but he is also describing the entire conceptual art movement. Starting back with Duchamp’s Fountain, certain artists turned away from the objects they produced and focused instead on the idea and the process. Throughout the 20th century, there have been conceptual iconoclasts that do more to challenge art than contribute to its so-called “progress”. Artists like John Baldessari, Joseph Kosuth, and Piero Manzoni all focused on the functioning and negotiation of art, and let the product of that process simply be a marker or a byproduct of the process.

Ebert’s reaction to Warhol was not uncommon. Abstract expressionism was supposed to be the art of the 20th century. Representational images were over. America was seen as finally engaging with the “fine art tradition” of Europe. Pollack was our Picasso, but Andy came along and ruined everything. Instead of building in line with art’s trajectory, he veered in an entirely different direction. Just as his Brillo boxes still seem out of place in a museum, so do his movies seem out of place in the history of cinema. Warhol does not belong to the new wave cinema, or porn, or independent film. He is an outlier, an aberration.

Ebert writes, “Warhol certainly isn't a director. He doesn't even seem to exercise enough conscious control over his films to be called a filmmaker. His primary function, apparently, is to be present when his films occur.” Ebert is right. Warhol isn’t a director, he’s an orchestrator. He organized situations that would produce interesting, challenging, and novel results. He, himself, was a product of this experiment. He cycled through personae; one day a vapid diva, the next a bohemian artist from the mean streets of Soho, then a queer hipster, or an asexual bon-vivant, or even a naive midwesterner from Pittsburgh. He wasn’t a director, nor was he a painter or a sculptor. Silk-screening soup cans isn’t painting.

His silkscreens are very similar to his films. His repeated grid of Marilyn Monroe relentlessly reproduces her likeness until it begins to degrade and lose its glamour and purpose. The misaligned, punchy, bright colors give way to blotchy black and white. He’s illustrating the process of how a woman becomes an image, and how an image becomes a product.

Film is a repeated image as well. It, too, is an illusion that can generate glamour and fame. It is a tool through which capitalism can turn a person into a product. Warhol generated the Monroe image by breaking several rules in the silkscreen process. As a result, the image fails to be a little photographic record of a movie star, and instead is smeared ink on a canvas. It cannot transcend its being an object, nor function as a proper image. In the image, the silkscreen process can do nothing but refer to itself. Warhol brings the same idea to film. He is not trying to transport us into a fictional narrative. He wants us to see a movie, not watch a movie. He wants us to sit in front of the screen and see the images as things, as if we are regarding an object.

Warhol’s 8-hour film Empire is spooled onto an enormous reel. When I saw a showing of the film, the reel was as compelling as the image it produced. These early films like Empire , Haircut, Sleep, and Blowjob are less about delivering a story and more about being a film.

Narrative wouldn’t play much of a role until Warhol began working with Paul Morrissey. Together, they created a halfway mark where the familiarity of narrative film could mix with Warhol’s unique approach. In the trilogy Trash, Flesh, and Heat there are storylines, even if some of it is spontaneously improvised. Story or not, all of the techniques of filming are kept so rough that they constantly draw attention to the fact that we are watching (seeing) a film.

Godard’s jump cuts, as seen in films like Breathless, are softened by their being uninterrupted sound, or by his never jumping while someone is talking, whereas Warhol cuts as if he is blindfolded. Dialogue, sound (ambient or otherwise), and movement are all ignored, and the film is randomly spliced. The result is not only to remind us that we are watching a film, but by deleting words, we get something closer to poetry than prose. Instead of a logical progression of statements, the dialogue becomes less rational and more associative. In Chelsea Girls, Warhol places two screens side by side and allows the juxtapositions of two films to randomly create associations while, at the same time, denying their ability to be coherent.

There is another layer to these more narrative films. Unlike Warhol’s earlier films, the narrative element allows for the subject matter to play a larger role in the film. We get to see interactions and listen to dialogue.

To find his actors and actresses, Warhol gathered together a crew of marginalized people who did not often get depicted in the media. We watch trans people, prostitutes, drug addicts, transvestites, and outcasts come together on screen and create characters that are more non-fiction than fiction.

The depiction of the dispossessed has long been a trend in art. Beginning, perhaps, back in the 16th century with Caravaggio, artists have been coaxing art down from its lofty depictions of angels and saints to the life of us everyday mortals. At the turn of the 20th century, there were the ashcan painters. Robert Henri and his rabble painted the underbelly of New York City under their motto “art for life’s sake”, as opposed to “art for art’s sake.”

The line between art and life was completely blurred for Warhol and his entourage. Just as Warhol was not a director, people like Joe Dallesandro, Candy Darling, and Edie Sedgwick were not actors. They were representatives of a world kept secret and apart from society. They gathered to mingle at Andy Warhol’s studio, which he famously named "The Factory". As a factory, it functioned less as an artist’s studio and more as a relentless satire of the junction between artists and capitalism. It was also a chaotic vortex where outsiders could gather and cross-pollinate.

Warhol brought Morrissey to The Factory and supplied the music, drugs, sex, and absence of boundaries that became the breeding ground for their films. They made hundreds of them, many more than are available. The sheer number meant that there was a camera rolling almost all the time, whether something scripted was happening or not. It all went into the mix.

In an interview about Warhol, his friend John Waters said, "Except for Duchamp, nobody has been more influential than Andy. Every artist who comes up today is infected by him in some way. You can't not deal with it.” Warhol’s influence, and Duchamp’s as well, may be more limited than Waters claims. What both men were doing was very far removed from their contemporaries. Andy Warhol’s peers like Lichtenstein and Oldenburg had superficial similarities, but what Warhol was doing was far more than Pop Art. Duchamp made some cubist paintings, but his bottle rack does not fit well into Gardener’s Art Through The Ages.

Warhol and Duchamp are important and influential culturally. In fact, they may be among the most important artists of their respective times, but it is difficult to locate their legacy. In many ways, they worked in opposition to the art world and so, by their own design, limited their influence. After Duchamp, the art world did not stop and rethink its purpose. It went back to painting. There were the Dadaists and the Surrealists, but they had their own ideology and mission. After the Second World War, these movements were a memory, and Picasso came roaring back into vogue.

Warhol was really the first true re-emergence of Duchamp’s sentiment. After Warhol had his day, it is unclear who his inheritor is. Jeff Koons is an obvious choice, but he didn’t further Warhol’s ideas very much. In a broad sense, both Duchamp and Warhol had such a profoundly insightful understanding of how culture functioned that it is hard to match. They contributed invaluable insight into the understanding of the modern world, but not many followed in their footsteps.

Nowhere is it more apparent than in the world of film. It is hard to identify a film that exhibits Warhol’s influence save, perhaps, John Waters’ filmography. It could be said that Warhol helped loosen the grip of the classic Hollywood style, but Godard and Cassavetes deserve more of the credit for that. When asked to name “film directors influenced by Andy Warhol”, Google came up with Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, Truman Capote, Ben Shahn, Tom of Finland, and Jack Smith. Smith is the only filmmaker in the bunch.

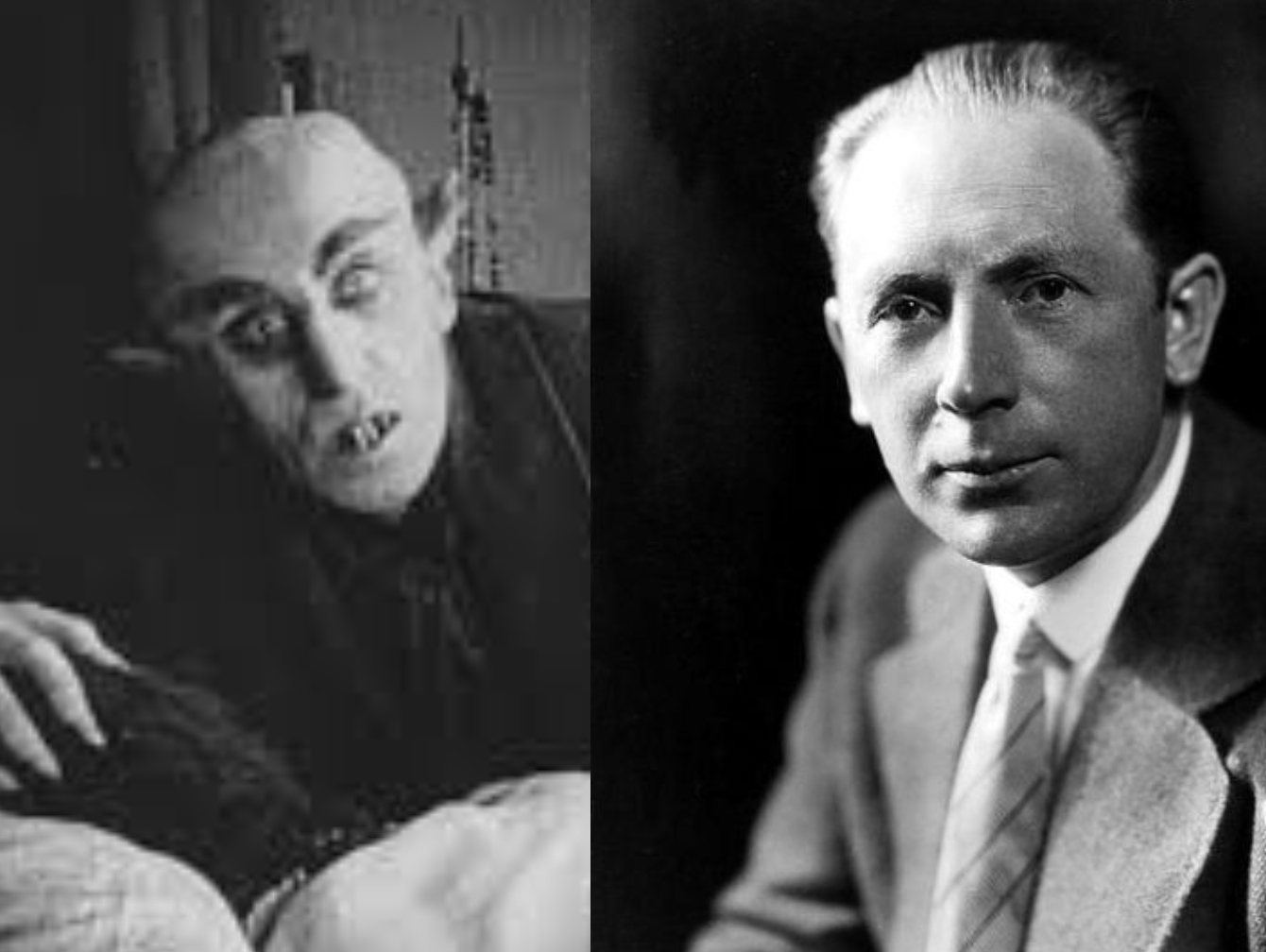

Warhol once interviewed Alfred Hitchcock, and never once did Warhol ask Hitchcock about film. Warhol asked questions about murder and why people do it. Warhol wasn’t interested in film or filmmakers. The interview became another opportunity for satire and the presentation of Warhol’s persona. At one point, he told Hitchcock, “Well I was shot by a gun, and it just seems like a movie. I can’t see it as being anything real. The whole thing is still like a movie to me. It happened to me, but it’s like watching TV. If you’re watching TV, it’s the same thing as having it done to yourself.” This quote illustrates the heart of what Warhol is doing. He throws himself into the mix, so that his life, his artwork, his ideas, reality, and fantasy are inextricably mixed and remixed until they are indistinguishable. There is no line between the sincere and the satire for him. This can be said of his films as well.

Warhol’s friends, like Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis, had already taken on performative personae. Their conversations defied simple discourse and created something that was both reflective and reflexive. The gossipy clutch of trans people in The Factory played at creating exaggerated female stereotypes, but at the same time, they relayed a bitter recrimination toward gender roles and conventional society. They sincerely identified with the opposite gender, but they also parodied it. Not only that, but they parodied themselves parodying it. It's an infinite regression of sincerity and satire.

In the film I Shot Andy Warhol, Warhol instructs one of his actors to “do something modern.” Whether this actually happened isn’t really important, I doubt Andy would care. What is important is that it is representative of his attitude. It is absurd and even stupid, but also an incitement to both revel in and mock contemporary society. Warhol once said of himself, “I am a deeply superficial person.” This contradiction reflects the tension between producing art and producing salable objects. His films were meant to be both.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/john-waters-mondo-trasho