Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window and Roman Polanski's The Tenant are both films about observing and being observed. Rear Window was released in 1954, and The Tenant was released two decades later, in 1976. The differences between the films reflect not only the difference between Hitchcock and Polanski, but also the changes in social and cultural attitudes between 1954 and 1976.

In Rear Window, we have a clear-cut narrative supported by a straightforward linear plot. As a protagonist, Jeff is admirable for the most part. He is clever, resourceful, and despite being a little world-weary as a reporter, he is good-hearted. As is typical of Hitchcockian protagonists, Jeff’s natural curiosity creates a slippery slope of voyeuristic tendencies that ends up embroiling him in a situation he cannot control. James Stewart would also go on to play such a protagonist in Hitchcock’s Vertigo in 1958. In Vertigo, his character gets embroiled in a web of deception, with what begins by simply watching a young woman. Vertigo, like most Hitchcock movies, ends with a rerun to stable normalcy. In Rear Window, Jeff is saved and his theory vindicated. In both films, the end provides closure and all is well with the world.

Polanski’s protagonist, Trelkovsky, lives in a much more confusing world. In Rear Window, all the neighbors are funny, quirky characters. In The Tenant, everyone seems far more sinister, even menacing. In addition, Trelkovsky is not safely hidden away in his apartment. Rather, he has to come outside and interact with his neighbors. His relationship to them is far from objective. We, as the audience, don't know if we can trust what we see through his eyes. In Rear Window, Jeff’s telephoto lens is a scientific instrument assuring us that what he sees is accurate, even if Jeff might be misinterpreting the data. Trelkosky is a much less reliable character whose anxious subjectivity is right on the surface. As a result, The Tenant does not have a straightforward master narrative that ties up all its loose ends. It leaves us confused and unnerved.

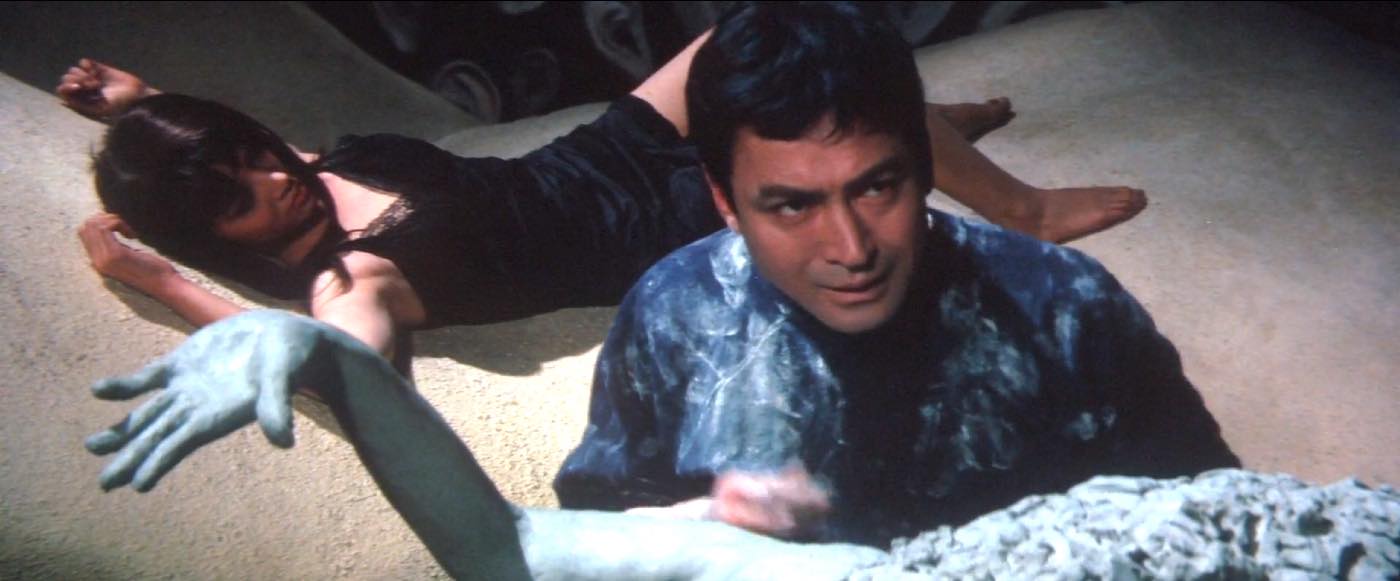

Both Jeff and Trelkovsky end up falling from their respective windows. Both are temporarily rendered helpless and lose their status as observers. The observer becomes the observed. Jeff's fall exposes him to the outside world. However, Jeff’s exposure really begins earlier, when the man he thinks may be a murderer, Mr. Thorwald, looks directly into Jeff’s camera. It’s an abrupt and frightening shift where the unwitting objects of Jeff’s scrutiny suddenly break Jeff’s remote objectivity.

Thorwald looks directly through Jeff’s lens, which means Thorwald is looking directly through Hitchcock’s lens, which means Thorwald is looking directly at us. Technically, Thorwald is breaking the fourth wall, but it is in the service of putting the audience on the spot. We have been caught. We are confronted with our own voyeuristic tendencies.

Hitchcock, his obligatory cameo aside, stays behind his camera, similar to how his character, Jeff, stays behind his binoculars. Hitchcock is a controlled and detached director who sees his actors as chess pieces he can manipulate. Each character has a specific purpose in a meticulously crafted and carefully controlled narrative. Polanski has no such objectivity. He literally positions himself inside his film by acting the part of Trelkosky. As the director and the lead actor, he must be the observer and the observed. The controller and the controlled. It’s a möbius strip of subjectivity, where an ordered narrative like Hitchcock’s is hopelessly lost in layers of confusion and anxiety.

In a scene in The Tenant, Trelkovsky is lying drunk in bed while a woman, who is also drunk, tries to undress him. While she wrestles with his pants, he mumbles a soliloquy about identity…

“At what precise moment does an individual stop being who he thinks he is? Cut off my arm, right? I say me and my arm. You cut off my other arm, I say me and my two arms. Take out my stomach, my kidneys, assuming that were possible, and I say me and my intestines. Follow me? And now if you cut off my head, what would I say, me and my head? Or me and my body? What right does my head to call itself me?”

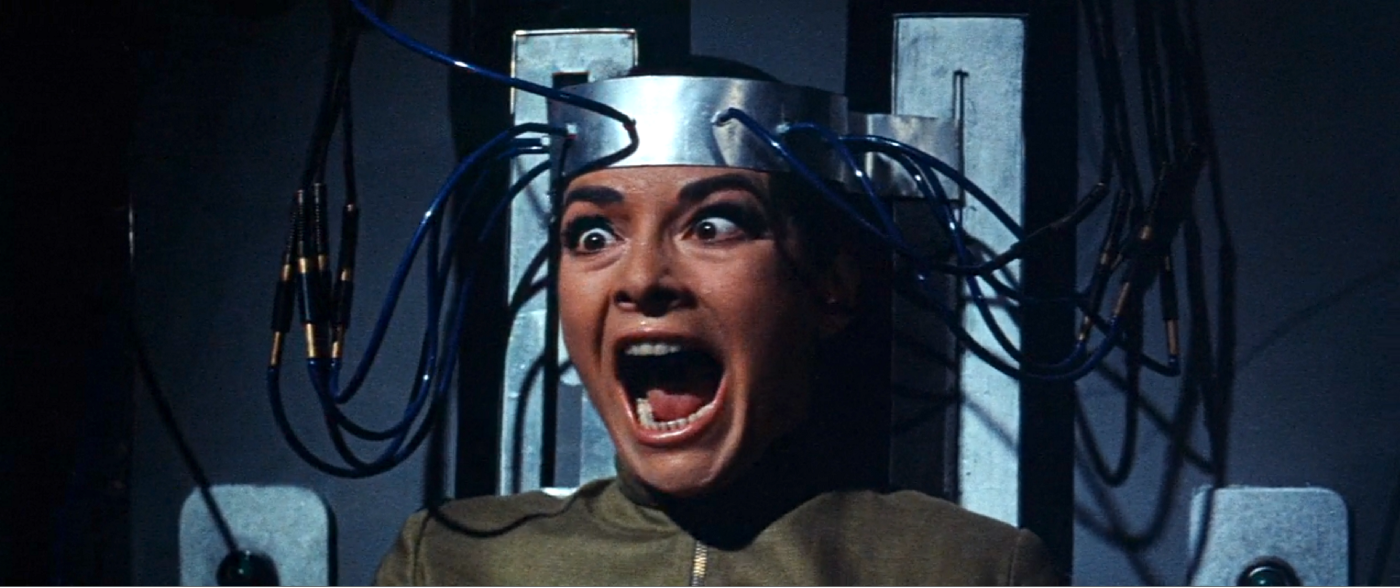

It’s an exercise in subjectivity. Trelkosky wants to find the boundaries of the self. When he follows his little mental exercise to its conclusion, he ends up decapitating himself, which, of course, foreshadows a later vision he will have and, in the end, his own death. The woman, Stella, is trying to engage him in bodily pleasures, but he has alienated himself from his own body. She is trying to unite her body with his, but his anxiety and confusion are causing him to dissociate and lose track of himself.

In Rear Window, Jeff, too, is being courted by a woman, and he, too, keeps her at bay. Both men suffer from feeling marginalized, but Trelkovsky’s alienation stems from something deep and abiding that is coming to fruition. Trelkovsky doesn’t understand what is happening to him, but he knows he is struggling. Jeff, on the other hand, feels aggravated, but lacks any insight into what is happening to him. He snipes at his girlfriend and the nurse who takes care of him. He passes judgment on everyone around him and never turns inward to examine himself. The binoculars are always trained away from himself. In addition, no one, until the very end, looks back at him, whereas Trelkovsky is constantly under surveillance. He is acutely aware of his observers and their oppressive judgment. Where Jeff is aloof and removed, Trelkovsky is embroiled and vulnerable.

Jeff is troubled by those around him who do not recognize the truth of what he is saying. Trelkovsky is completely confused and cannot find the truth. When Trelkovsky finally thinks he has, it destroys him.

This is where the difference between 1954 and 1976 becomes apparent. One way to view the ideological history of the twentieth century is a slow erosion of our faith in rationality and progress. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, written in 1801, she described her anxiety concerning the faith we place in reason, logic, and science as our ultimate saviors. Hitchcock flirts with this anxiety. He likes to plumb the depths of the subconscious and dredge up interesting and fearful ideas, but they always end up resolved and safely put away in the end. Hitchcock has faith that society at large can contain its deviants and transgressors without falling apart. To be fair, he was also dealing with studios and officials who constantly threatened to censor him unless the genie was put back in the bottle by the end of the film, but this, too, is a function of the time.

By 1976, the rules of censorship had drastically changed, but so had society in general. The riots and revolutions of the 1960s had shaken much of the faith that people had placed in authority. The world seemed like a far more chaotic and frightening place.

A few years prior to making The Tenant, Polanski’s pregnant wife was stabbed 16 times and her blood used to scrawl “pig” on her door. Her murder at the hands of a cult, headed by a madman, surely contributed to Polanski’s creation of The Tenant. His own feeling of vulnerability made a character like Jeff completely impossible.

Jeff defines himself in opposition to his surroundings. He doesn’t see himself as yet another window in the array of windows. Instead, he distinguishes himself as the detached observer above the fray. In the end, Jeff’s identity is left unchanged, and those around him must accept him as he is. He learns no lesson.

Trelkovsky has no such independence. By the end of the film, the boundaries of his identity are in complete disarray. He can’t differentiate between his thoughts and the thoughts of others. Even his relationship to his own body, as foreshadowed by the earlier quote, comes into question. Unlike Jeff, he is unable to find himself amidst those who surround him.

The two films outline the nature of objectivity and subjectivity, just as they define identity as a position one takes in acceptance or rejection of other people. Rear Window has a fundamental optimism that objective truth can win the day and that deviant behavior can be dealt with. No such optimism exists in The Tenant. No hero’s journey here. The subjective overtakes us and we are overwhelmed by a world that will not succumb to our control.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/the-unacceptable-truth-of-compliance

[…] that behind every door there is a bizarre idiosyncratic fantasy aching to be fulfilled. From Hitchcock’s Rear Window to Lynch’s Blue Velvet, we are all curious about what our neighbors are doing behind the […]