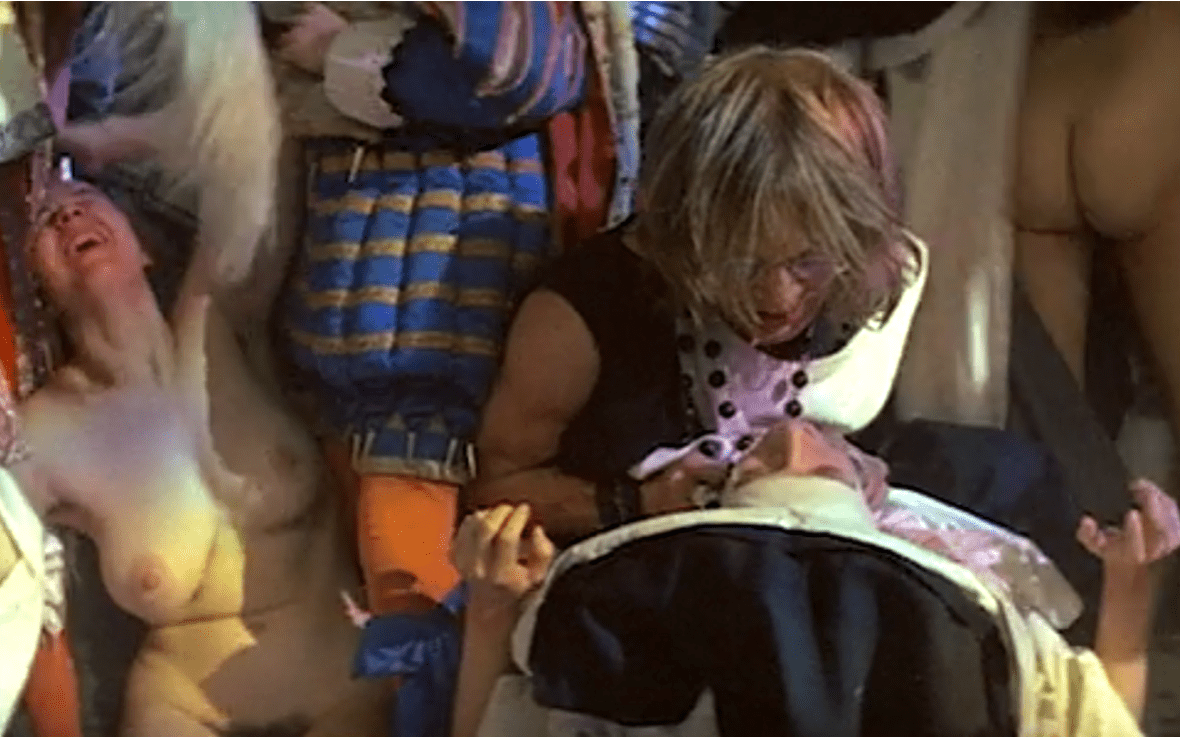

How about a mix of Peter Greenaway, Pier Pasolini, Kenneth Anger, and Pierre at Gille? Maybe add a little Alejandro Jodorowsky and a Joel Peter Witkin too? Whatever Ulrike Ottinger has wrought in making her film Freak Orlando it is not an easy cocktail to sip.

Freak Orlando was made in 1981 in Germany. Queer culture had yet to face AIDS or Ellen. In 1981 there was no united LGBTQA+. Even though all of these groups were individually challenged and marginalized, they were far from united. Efforts at recognition and/or civil rights often ended up pitting groups like transexuals against homosexuals. Some identities like asexual had yet to even be formed or understood.

Queer art as a movement had yet to really form. It was shoved in a cultural closet, but the isolation only intensified queer artist’s intensity. For many of them, there was no point in trying to be socially acceptable. If you were going to break out of the closet you might as well embrace your outsider status and face mainstream society head-on. This does not describe all queer expressions from the early 80s but artists like Pasolini, Warhol, and Waters could be explosive and confrontational. These men were not interested in subtlety or integration, they were ready to break down the door.

Ottinger’s contribution to the revolt was Freak Orlando. Her film is subtitled “Little Theater of the World told in 5 episodes.” The film’s framework is a historical tour of western culture, but the framework is not an orderly, chronological survey. What Ottinger gives us is a kaleidoscopic, hallucinatory trip through the ever-changing concepts of humanity, sex, religion, and the human body.

The film has the feeling of a Weimar-era cabaret. After the end of World War One, a new level of permissiveness and acceptance opened the door to a wide variety of expressions, especially in Berlin least. Acceptance of homosexuality was buoyed along with this new liberal atmosphere. Ottinger harkens back to the colorful, celebratory, feelings of this time but as in films like The Tin Drum, the undercurrent of the impending Nazi wave can be felt like a dreadful undertow inexorably gaining strength.

Ottinger is not interested in a chronological survey of homosexuality through the ages. She freely mixes images, issues, and time periods so that she can find resonances and connections. A coherent narrative would parse everything into discrete entities that would undermine her purpose. Freak Orlando is driven more by collage than plot.

Weimar culture along with queer culture was twisted and eventually destroyed by the fascists and when it was all over things did not simply go back to normal. When the Allies won the war and came to liberate the concentration camps the homosexuals were not freed. They had to stay incarcerated for the full term of their sentences.

Added to the depictions of Weimar liberalism and the nazi oppression, Freak Orlando mixes in S&M and leather-men. The sexual play of domination and submission easily blends with nazi politics. Even before Ottinger made the connection the leather-man aesthetic often included a Nazi SS hat.

Pasolini’s Salo came out 6 years prior to Freak Orlando and it looms large in Ottinger’s vision. In movies like Salo and Pigsty, Pasolini found a connection between Aryan aesthetics and homoeroticism. The Nazi obsession with the perfect man, Nietzsche’s Übermensch, belied a sexual fascination with the male form.

Ottinger explores the relationship between the human individual body and the state. The ideology of fascism was expressed in flesh and blood. The grandiose vision of a new utopia had concrete, corporal consequences.

Ottinger also inserts numerous references to the Spanish Inquisition. The inquisitors and the Nazis have a core commonality, bureaucracy. The body becomes a number to be filed. Citizens are counted, alphabetized, and categorized. Then certain categories are deemed unacceptable and in both Spain and Germany that meant Jews and homosexuals.

This categorization of humanity is what creates the homosexual. The idea that our desires define us and can be used to label us creates these terms. Even today “gay” is sometimes used as a noun instead of an adjective as in “he is a gay.”

Today in order to combat these labels there is a movement to splinter the terms into smaller, more specific terms evidenced in the rise of the label LGBTQA+ or Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Queer, Asexual, and others. These labels do not challenge the system of labels but simply try to make it more accurate. The idea that we can be labeled and shunted into categories remains unchallenged. Ottinger herself back in the 80s registered her disapproval of what she termed “being put in a little drawer.”

The word “freak” in the title Freak Orlando also invokes a much broader umbrella classification. It encompasses all those who deviate from the norm. The concept of the freak is as old as history. In Ancient Greece, they were ejected from the city in order to purify the citizens. The Nazis killed anyone with physical differences: people with down syndrome, cerebral palsy, dwarves, the mentally or physically disabled, anyone who could be seen as different. Near the end of Freak Orlando, we see the protagonist, Orlando, acting as the master of ceremonies at an ugliness contest. He/she announces into the mic “Beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror.”

Like Joel Peter Witkin, Ottinger uses “distortions” of the human body to draw attention to our mortal nature and our grounding in the corporeal. This also ties to how sex, gender, and sexual preference labels are rooted in or connected to our physical bodies. Near the end of the film, one of the characters says “In the land of the lame limping is the custom.” This speaks to normality being a subjective societal construct. Ottinger reveals that all taxonomy is political. In addition, all aesthetics are political as well. For Ottinger, the beautiful and the normal exist in order to define the ugly and the deviant.

Layered into all this German history is yet another narrative. Ottinger also incorporates Geek mythology throughout the film. There are references to Narcissus, Zeus, Hermes, Janus, and the Cyclops from the Odyssey.

The heroic male of Ancient Greece fits easily into Freak Orlando’s cocktail. The struggles and tragedies of the idealized, eroticized male, points both to humanity’s beauty as well as its horror. Classical tragedy requires a celebration of beauty and strength and a recognition of its limits. Before Icarus falls to his death he must first fly higher than anyone before him.

Early on in the film, the cyclops is seen making shoes for futuristic consumers in a space-age mall. One of the customers complains “These mythological sandals don’t fit.” This comment can have several different meanings but it reveals a mismatch between our ideals and the world in which we live. It reveals the gap between our ordinary, human bodies and the sculpted marble paragons that stare down at us from pedestals.

The film’s title refers to Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando. In both Wolf’s novel and Ottinger’s film, the lead character transcends time, as well as gender. Orlando never ages and he/she sometimes switches gender. Orlando searches for fulfillment in an unstable world where the changes in society reframe issues of the body and identity-making self-actualization a moving target.

We do not normally live long enough to see major shifts in history, but Orlando, in both the novel and the film, accumulates history in his/her body and mind. Physically he/she both transforms and stays the same. His/her mind is a single continuous conscious identity. His/her body changes gender but it does not change its age. Even if he/she did not change gender by existing through the ages, what it means to be male or female changes. It’s a möbius tangle of identity and social context that allows endless combinations of the concepts at play.

With all of its rich imagery and imaginative pageantry, Freak Orlando tends to ramble on. The many celebration scenes and ceremonies eventually wear thin. It is an ambitious film with a wide scope. With so much going on it can be disorienting, but in the end, it is only through confusion that we are forced to think. Our brains are always trying to save energy and find short cuts. They need to be cornered and disoriented if they are going to actually be made to work. Otherwise, we glide along on tried and true associations and expectations. If nothing else Freak Orlando certainly defies expectations and challenges the norms of culture and society as well as film

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/john-waters-mondo-trasho