In the span of just two years, 1972 to 1973, a series of four films were made in Japan by The Toei Company. The first three were all directed by Shunya Itō, and all four starred Meiko Kaji. The series was based on a manga by Toru Shinohara. The four films make for an astonishing group that incorporates an amazing array of techniques and approaches to filmmaking.

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion (1972)

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion was director Shunya Itō’s debut in the film industry. Of the four films this one is the most likely to fit the expectations of the ticket buyer. Naked women are on display almost immediately. We are treated to sadomasochistic scenes, lesbian sex, torture and general bullying. Its all just what you would expect of any film in the women in prison genre. However just as the film fulfills expectations right from the start so does it exceed those expectations. The cinematography, the fauvist lighting, the extreme angels and close ups, all let you know right away that you are witnessing something out of the ordinary.

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion is certainly a sexploitation film and therefore lessoned by its simplicity and exploitative nature. It is very creative and even smart in many ways but it is also dragged down by its misogyny. It is far better than Caged Heat, Chained Heat, Black Mama White Mama,The Big Doll House or any other film in the genre, but that does not preclude it treading on some of the same degrading territory that the others do.

However Amidst the genre tropes there are impressive and wonderful moments.There is a shower scene that turns from licentious voyeurism to a demonic kabuki in the flash of an eye. Matsu is being chased by a fellow inmate when suddenly, as if possessed, the inmate turns bright turquoise and her face transforms into a demon mask. Nothing is explained its just thrown at you as if it belongs in the reality of the film. Its audacious moves like these that elevate this first film beyond sexploitation, but its the next two films where Itō’ really shines.

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (1972)

If a movie goer bought a ticket to see Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 expecting a continuation of what they had seen in the first film they were in for a surprise. No nude ladies in the shower here. There is very little nudity at all, save the scene when an inmate hikes up her shirt to reveal the scar on her belly where she stabbed her unborn child to death. This is an entirely different movie than its predecessor.

In a 1997 interview Meiko Kaji the lead actress, said, “the consciousness of each successive film became more and more grotesque, more radical, just to maintain the audience, to make sure the pictures were a hit.” Often in sequels the way filmmakers “maintain an audience” is through more nudity, sex, explosions, blood and car chases, but in this case Itō choose to decrease all of those things and to push cinematic experimentation even further instead. The films get increasingly more artificial, mannered and abstract.

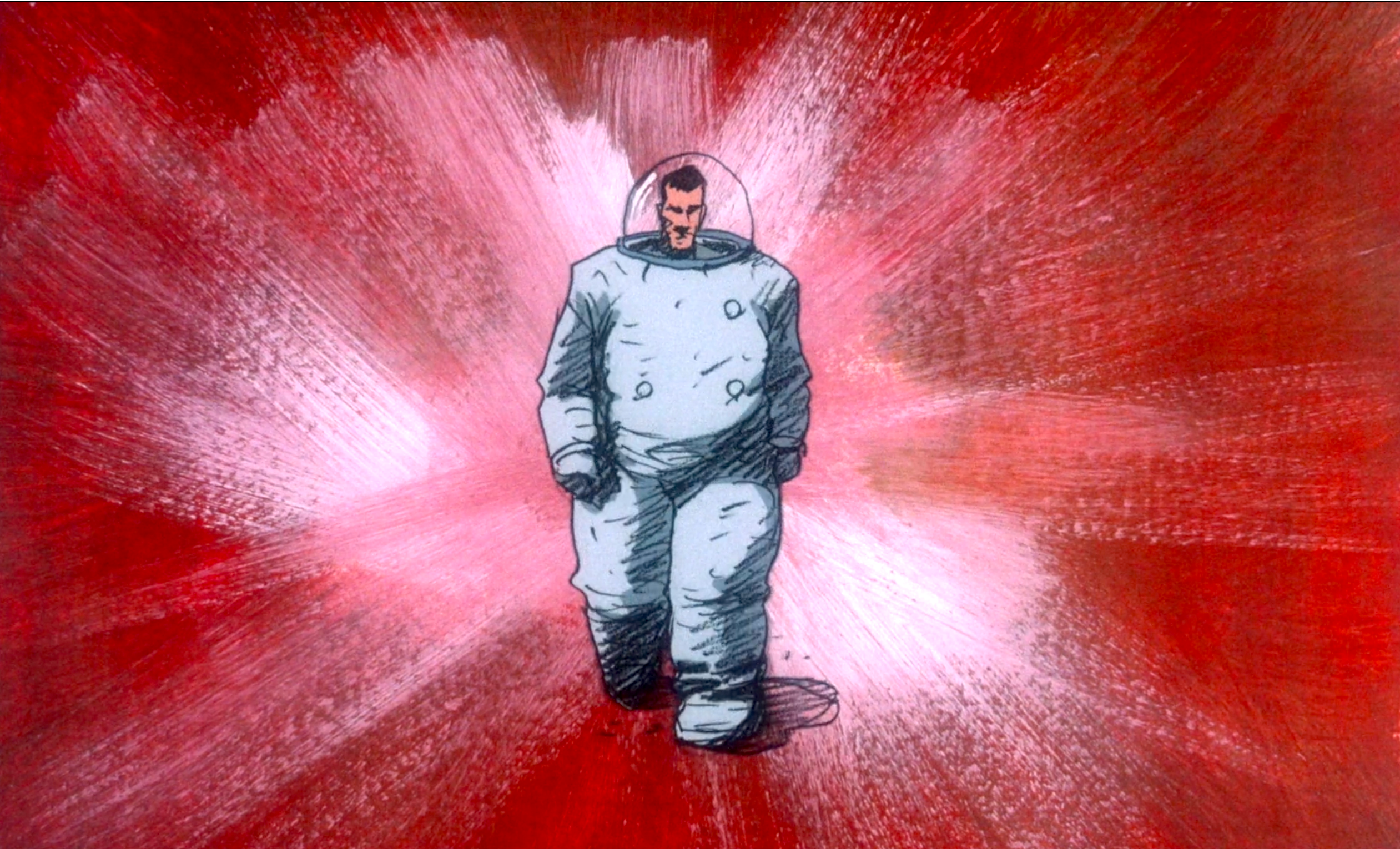

The cinematic ideas in this second film are bold and beautiful. Our stone cold heroine, watches an old woman die in the forest. When the old woman takes her last breath a neon purple light turns her body into a luminescent vision. Then a storm of multicolored fall leaves explodes on the screen and cover up the body. The wind dies down and Matsu removes a knife form the old woman’s hand. With her dreadful and determined face Matsu watches as the wind rushes back and blows away the leaves to reveal that all traces of the dead woman are gone. Suddenly the forest and all its leaves turn to grey and we stare at Matsu, the Scorpion, standing in a colorless landscape. She slowly waves the knife in front of her eyes and the wind returns one final time to torment Scorpion’s hair. As her hair comes to life it is lit by the fall colors that are missing all around her. Its breathtaking!

The film is full of surprising bursts of beauty and deeply courageous experiments that create exciting cinematic passages. Watching Citizen Kane it becomes obvious that the film was meant as a portfolio of everything Welles was capable of. It is very impressive but the overall effect can feel cold. Instead of a deep investment in the characters and acting we get a tour force of camera angles and editing. Not so with with the Scorpion films. There is an ecstatic revere unfolding in these films. They are ambitious like Citizen Kane in their creative variety but they hold together as a poetic, baroque whole.

As for Matsu, she is almost completely silent in all four films. Meiko Kaji’s portrayal is amazing. Not only does her character not speak, her face almost never moves from a dead, affectless stare. It sounds cliche but its all in here eyes. She changes their shape, she changes how open they are, she changes how often she blinks and with just that as a basis of communication she delivers a profoundly powerful performance.

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable (1973)

This film does not take place in a prison and so it has no anchor to link it to one genre or one set of expectations. There are noir elements and posturing yakuza elements, there are the sexploitation and prurient violence elements, and a kind of Wild at Heart/Wizard of Oz thing going on as well. It is even more broad in its approach and scope than its predecessor.

The opening scene is just astounding. We see Scorpion dressed in ordinary clothes sitting on a subway car amongst a crowd. The police enter the car and try to catch her. In the process the ranking officer manages to handcuff her arm to his, but she lunges out of the car just as the door closes. The policeman’s arm is stuck in the doors and so she hacks it off with a carving knife. The opening credits of the film roll while we watch her run through the streets with a severed arm cuffed to her wrist. It flaps wildly as she runs leaving a trail of shocked pedestrians in her wake.

As before this film is made with passionate abandon. They try out everything. There is a scene in a bar with so many jump cuts it starts to look like stop motion. There are passages done in negative, hyper-close ups, theatrical lighting, but never does Itō lose control of the film. It is all presented with consummate skill and careful attention. These grainy films may be churned out on cheap budgets but Itō doesn’t let it get in his way.

In the middle of this hurricane of a film there is profoundly beautiful moment of transcendence worthy of Tarkovsky. My jaw actually dropped open when I saw it. Matsu is hiding in the sewers and her friend, Yuki, is trying to find her. Yuki calls Scorpion’s name over and over through the manholes while dropping lit matches through the small openings. We follow from Yuki’s perspective but eventually we see Scorpion’s point of view and we watch while the plaintiff echo of “Scorpion” reverberates all through the dark tunnels. Then we see the little balls of fire fall. Its hypnotizing and just as you are noticing the beauty hundreds of little fireballs begin to float down from everywhere. There is no reason given, no explanation, its just an invitation to a beautiful reverie of sight and sound. Its a dream seamlessly mixed into reality.

Female Prisoner #701’s Grudge Song (1973)

The last of the four films was directed by Yasuharu Hasebe. Female Prisoner #701’s Grudge Song is not a bad film, but it isn’t that good either. There is some effort put into carrying on the visual innovation and excitement of the previous three films but this one just doesn’t quite pull it off. As a whole the film is more conventional and takes fewer risks.

The first three films had outrageous depth of field shots and vertiginous camera angles where as this film seemed far more shallow and balanced in appearance.

The Series

The films taken as a whole present a complex image of women. Most of the salacious material is in the first film but there is a little in each of them. Setting that aside for a moment we see a tangle of different ideas. The women are subject to a lot of abuse. This in itself is not a problem it is why the abuse is depicted that matters. It is clear that the suffering of these women is meant to make the audience identify with them. We come to understand their situation better and through it their motivations.

One of the most telling scenes occurs in the first film where Matsu is raped. To insure the viewer understands who’s side we are on the assault is filmed from underneath the floor as if it were happening on a sheet of glass. Her back is to the viewer and we see the grimacing rictuses of venial enthusiasm on her assailants as they tear into her. This is a depiction of rape that degrades the perpetrator. They look like feral beasts. There is no eroticism here.

Not all the scenes are as clear cut as this. Films that take as many risks as this are bound to cross lines, or redraw them, or eliminate them. The two middle films, Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41,Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable, manage to deliver a powerful message about women in society that could be seen as both dark as well as empowering. Matsu hardly ever speaks in these films, but her silence is not one of submission, its a Clint Eastwood silence. Some of the abuses she suffers are not so much oppression as they are an opportunity to highlight her hard as nails toughness.

This grand quadrilogy is unfortunately marginalized with labels like cult, Pinku, Grindhouse or Sexploitation. Its a shame that such a substantive and well crafted set of films doesn’t get more attention. A few of them are available on DVD and there is an out of print box set on Blu-ray, but films like these are in danger of disappearing under the overwhelming tide of streaming video.If you enjoyed this article you will probably enjoy this -

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/the-crimson-bat-blind-swordswoman-series