Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023), Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022) all share a common focus. They all try to picture what freedom would look like in a world where not only is anything possible, but everything is actual. In these films, we encounter what looks like freedom of choice, but every choice is simply a juncture that leads to every possible result. A choice where all possible outcomes come to fruition isn’t really a choice.

What this worldview means is open for debate, but in these films, this idea results in an existential crisis. These films question if agency is possible in a world of infinite consequences. In addition, they ask if our decisions are preset according to the trajectory of the particular universe we live in.

In Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Miles creates havoc because he is not respecting the predetermined nature of his universe. In Everything Everywhere All at Once, all the characters struggle against a feeling of meaninglessness in a world where everything is inevitable.

The particular facets of this issue are not the focus of this essay. It is only the fact that this issue seems to be raised with increasing frequency in our culture. Essentially, it comes down to a classic philosophical argument between freedom and determinism. To me, this dichotomy seems more like an issue of semantics than an actual problem. There are different ways to frame the debate. Considering what we know about human psychology, labeling us as either free or determined doesn’t make sense either way. In the three films, the psychology of choice is only half the problem. The nature of time, space, and entropy may indicate that everything is predetermined. All of this is made infinitely more complex by considering whether ignorance of our fate makes us free.

With the issues of freedom and determinism as a foundation or background, all three films explore what role morality plays in a predetermined world, or, in the case of the multiverse, worlds. All three films allow the occupants of different universes to meet each other. Actually, meeting the individuals that are generated by your choices, and being aware of how your decisions will effect them, makes morality impossible. Any action you make will bring disaster to some of them. Morality is canceled out by all options coming true. Without morality guiding our actions, we cannot attach any purpose or significance to our lives. This brings us back around to the existential angst that all three movies depict. By making everything come true, the multiverse assures that nothing matters. This is the heart of Joy Wang’s confusion and anxiety in Everything Everywhere All at Once. In an argument with her mother, she explains, “If nothing matters, then all the pain and guilt you feel for making nothing of your life goes away.”

Living in an infinite web of alternate you’s is not only a moral problem. These films also reflect a common fear and frustration with the intensity of identity politics. The existence of so many identity labels, so many possible identities, including “fluid” identities, can be overwhelming. We live in a world where every choice we make results in being labeled with a new term and a new set of expectations. Each person we associate with, each song we listen to, each pair of shoes we buy, comes with preset identities. Our peers will evaluate and label us based on every little move we make. So will all the algorithms on the Internet, each one trying to paint an increasingly detailed portrait of us. These unsolicited portraits then go on to shape what we are shown on our screens, creating an identity feedback loop. In these films, all our possible identities exist and vie for primacy.

Anxiety over identity politics is only one possible theme in a variety of issues these multiverse movies address. The writers and artists who made these films not only respond to the changes they see in society, but also to the changing nature of the media they work with. A society, and the media it uses to express itself, often reflect each other.

Artists today have an endless variety of tools and images at their fingertips. Creating impressive imagery is no longer a challenge. A portrait can be made, airbrushed, and optimized by anyone using a free app on their phone. A sculpture can be made at the click of a button on a 3D printer. Art has become so facile, it is changing what it means to be an artist. In fact, many artists have stopped calling themselves artists and refer to themselves as “content creators".

The term "artist" is a very general term, but it still indicates something about the attitude of the creator and how they see themselves. “Content creator” is an even less specific term. “Content creator” is a term born out of the economic ideology of capitalism. It deemphasizes the nature of what the creator is producing and puts the attention on the selling of it. It doesn’t directly indicate that the creator is selling what they are producing, but the term draws attention away from creativity and focuses instead on the generating of a product for sale. “Content” might easily be replaced with the word “commodity” or “product".

The distinction between an artist with a meaningful relationship to what they are producing, and a capitalist generating imagery for money, is not so cut and dried. There is a very large area of blurry overlap. Most artists are a blend of the two, but while it is easy to see that some sincere artists are, to some extent, influenced by money, “content creators" often seem unaware that, regardless of their intention, the content they are producing is still meaningful. They may think they are just making a video about how to shape your eyebrows, but there is an ideology and worldview that are still being presented. All imagery is ideological. All production, artistic or otherwise, is ideological. A video about eyebrow threading carries along with it ideas about aesthetics, gender, power, the influence of peer groups, identity, normalcy, the relationship between pain, submission, and beauty. It is a powerful cultural primer contributing to a worldview that is forever in flux.

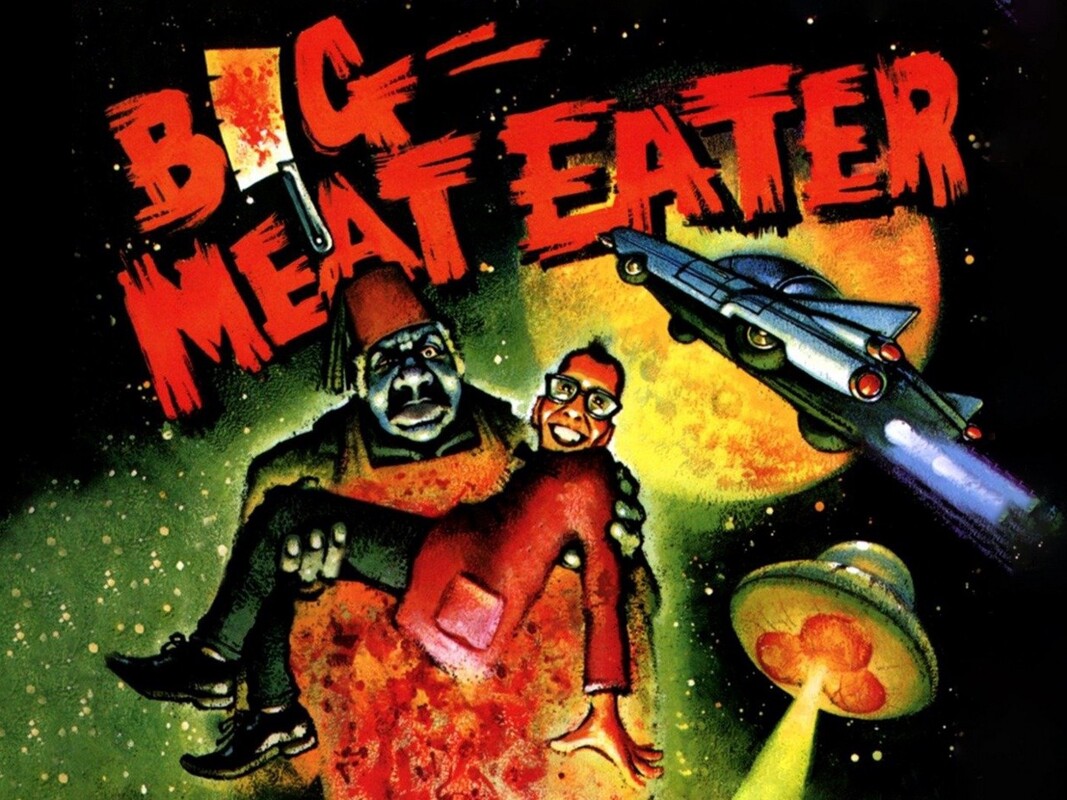

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (SMASV) is a mix of reactions to the myriad of possibilities presented to us by society, as well as the myriad of possibilities that an artist faces in the world of CGI, AI, and billion-dollar movies. Whether you refer to it as content, art, or a product, SMASV, and the other films, are celebrations of all that is possible in the world of cinema. It truly is a depiction of everything, everywhere, all at once. I’ve never seen anything that comes close to the visual density of SMASV, but as I was watching it, I kept thinking about Michelangelo and the enormous painting he made on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in 1510.

1510 is near the end of what historians call the Renaissance. The first quarter of the 16th century was a transitional period between the waning classical purity of the Renaissance and the odd excesses of the Baroque era. This transitional time is sometimes referred to as the mannerist period. A time when many artists felt that painting had reached its pinnacle. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael spent the second half of the 15th century in pursuit of perfection. The perfect body, the perfect proportions, the perfect composition, the ultimate attainment of pure beauty and harmony. This pursuit eventually ran out of steam. Either artists lost faith in the existence of such perfection, or felt that painters like Raphael and sculptors like Michelangelo had attained it, leaving little reason for continuing on. Many felt that art had reached an impasse.

When Pope Julius II forced Michelangelo to leave Florence and come back to Rome to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, Michelangelo did something unexpected. What he painted there in that room was not what the Pope asked for. In fact, the Pope and Michelangelo fought over it constantly. The Pope even beat Michelangelo with a cane. Michelangelo’s painting is often singled out as one of the first mannerist pieces. Mannerism was a strange style. It was a way of deliberately challenging an artist who had mastered his craft. It was a demanding approach that required the ability to render the human body with perfect accuracy, while simultaneously being able to distort and shape it in unexpected ways.

The Sistine Ceiling is a good example of this. It is a ridiculously complicated and difficult series of paintings applied to the ceiling with the most difficult of media (fresco) by one man lying on his back. The figures depicted float above the room in an assortment of the most challenging poses and angles possible, as they tumble and fly through the heavens. Michelangelo illustrated the entire Bible from Genesis to Revelations, ending with a terrifying 45-foot-tall depiction of the last judgment on the altar wall. Included in this final image is a self-portrait of Michelangelo as a hunk of flayed skin being carried away into the clouds. (See below)

Michelangelo had forsworn painting when he moved to Florence. Painting the Sistine Chapel, for a Pope who already hated him, allowed Michelangelo a kind of freedom. He knew that whatever he made would meet with disapproval, so why not use his skills to create something challenging and new?

Like Michelangelo, the filmmakers behind Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness had an endless array of powerful tools and a giant pile of money that allowed them the freedom to not only create imagery, but to do it with ease. It is hard to challenge yourself as an artist when you have AI, CGI, half a billion dollars, and a legion of artists at your disposal, but all that power creates a challenge in and of itself. If so much is possible, where do you begin and how far can you go? How do you take full advantage of all these opportunities? Such challenges are reflected in the depiction of the multiverse. The artists making these films have more than they need at their disposal, and it is reflected in the chaos of the multiverse they bring to life. Out of the movies mentioned, I’m not sure if any of them, save SMASV, really manage to fully exploit this plethora of possibilities. SMASV is so tightly packed with imagery that it becomes an assault on the eyes that stuns you with its intensity.

SMASV and the other films take super-powered tools as a given. Using them to create a realistic-looking fantasy world, like in Star Wars or Lord of The Rings, is not enough. It’s easy to make a fire-breathing dragon look real with what is available to well-funded artists. What SMASV does is push everything to its limit, even to the point of parody. I wouldn’t describe SMASV or the others as actual parodies, but they have a self-awareness that allows them to indulge in ridiculously ornate and complex visuals that playfully pile up until it all flirts with the ridiculous.

Michelangelo may have seen his roiling tour of virtuosic skills on the Sistine Ceiling as an attempt to infuse something that he now considered stale with new life and urgency. Certainly, no one in 16th-century Rome had ever seen anything as terrifying as Michelangelo’s Armageddon, or as openly sexual and bizarre as a depiction of God’s naked butt flying through the heavens. (See below)

Image makers today are drowning in a limitless, ever-growing sea of images that will easily swallow up anything you produce before anyone has a chance to even see it. What could a portrait artist hope to achieve with a brush and canvas, when over 300 million images are uploaded to Google every day? A title like Everything Everywhere All at Once makes perfect sense in the current world of art. It’s not a coincidence that a year before the film, Bo Burnham released a song with the chorus, “Anything and everything all of the time.”

How are any of us meant to live in this ever-changing onslaught of information? Trump left office in 2021, leaving behind a trail of trauma and destruction we will still be healing from for years to come. Trump, and his mentor Putin, used information the same way that the makers of SMASV used images. The idea was to overwhelm the recipient, leaving them stunned and passive. Several news outlets referred to it as a “firehose” of information. A firehose that knocks you down and leaves you helpless. What Trump and his sociopathic handlers wanted to do was completely destroy the public's ability to discern fact from fiction.

How do you conduct a productive exchange of ideas with someone who believes that 5G is out to get them, or COVID-19 was a hoax, or the Earth is flat? How do you discuss current events when Fox is screaming about Democrats sacrificing children to Satan? The Trump years are an “Everything Everywhere All at Once” blender that conflates truth and falsity until we can no longer discern the difference. SMASV and the other films can be seen as a reaction to this onslaught.

This brings us full circle, back to freedom and determinism. As the spectacle of society swallows everything around us, we become helpless spectators. We each come to believe that no matter what you say, or what you do, you will be drowned out by belligerent nonsensical chatter. Do you remember Steve Bannon, Paris Dennard, Kellyanne Conway, Trump Jr, and Sarah Huckabee Sanders? They were human firehoses used to cover over “Everything Everywhere All at Once".

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023), and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022) all have something else in common. They all came out at the waning end of a worldwide pandemic. According to the World Health Organization, 6,941,095 people died as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak that began in 2020. This world-changing event has to be factored into any analysis of cultural production during the early 2020s.

The concept of a multiverse and its effect on our significance plays directly into the anxieties produced by the pandemic. The relentless firehose blasting us with an overwhelming overload of information could be a metaphor to either describe our lives as internet spectators trapped in our houses unable to look away, or the feelings we experienced when we first emerged from our isolation.

Which is more overwhelming, living in a virtual world where every reality is smashed flat into a 3-minute video, or the real world with the unpredictability of real human contact?

With everyone isolated in their own apartments, proximity was no longer the driver for our shared experience. We no longer physically interacted with our coworkers, peers, or friends. To find human connections, we entered a sterile, abbreviated, non-physical, virtual space where, instead of seeing a cluster of friends and acquaintances out in a world of possibilities, we saw our own isolation reflected back at us in the eyes of others who were trapped at home just as we were.

The real world of COVID was barely visible. People disappeared into hospitals, businesses vanished, schools and streets were empty. There was nothing to see, but the world of the Internet, unchallenged by everyday experience, became increasingly real. Reality shrunk while the virtual world expanded.

The pandemic spurred big life changes, changes in identity. Many people changed jobs, changed partners, changed homes, and changed habits. The forced cocooning of the lockdown seemed to give people a chance to consider the other possible lives they could be living. Is it any wonder that our culture became obsessed with the concept of the multiverse?

Back in the 1500s, while Michelangelo toiled away on his oversized fresco in Italy, a man named Copernicus was formulating a theory that the Earth was not the center of the universe, but simply one planet among many, with no more import than any other celestial body. The significance of humanity was profoundly downgraded from a leading role in the center spotlight, to a lowly extra.

At the same time that our physical position in the universe was being challenged, our hierarchical position was thrown into question as well. The grand hierarchy of the universe proposed by the Catholic Church was threatened by the newly formed Protestants. The universe was not an immutable hierarchy with God at the helm and humans ranking near the bottom just above the animals. For Protestants, we each had our own direct line to God. He had a plan for each of us that we could negotiate with him directly. This concept caused a profound instability in the order of things.

These upheavals caused deep and unsettling changes across Europe. When Hugh Everett proposed the concept of the multiverse in the late 1950s, it had far less of an impact than Copernicus’ universe-shattering insight, but it continued the demotion of humanity. Not only were we no longer the center of the universe, but our universe was longer The Universe.

Copernicus told us that we were not the center of the universe. Darwin told us that we were not God's special creation, but simply animals. Freud told us that not only were we merely animals, but we were sick animals. Sartre told us that our sick, little animal lives had no meaning. Everett furthered this descent by telling us that our lives, our lived experiences, and identities, are only one version of an infinite rabble of possibilities.

SMASV and the other films are modern-day narratives designed to wrestle with this new status. Narratives are, at their heart, claims to efficacy. All stories are an attempt to show that we have agency. Stories connect a series of cause-and-effect events in order to provide some kind of meaning. The hero did X which caused Y which proves the moral of Z. Life in a multiverse means the hero did A, B, C, D, all the way through to Z, causing A through Z to happen, resulting in A through Z consequences. How do you make a story out of that?

What demotion is left for humanity to endure? I suppose you could turn to the work of Juan Maldacena at Princeton, who proposes that we are all just holographic projections. We’ll see what happens to narratives when movies transform into virtual holographic experiences that are not only indistinguishable from reality, but are reality.

If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy this - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/wakanda-for-sale/