You have to be in the right frame of mind to face down the movie Crazy Love. Its overall attitude is best summed up as “Fuck you.” It’s a sort of queer, Dada-style protest against everything. There is no plot, no dialogue, and the soundtrack is a collage of what have to be unlicensed snippets from the big hits of the ’60s including numerous Beatles songs which I’m sure were too expensive for such a film production to buy.

The wild nature of Crazy Love might have it associated with a number of movements like the surrealists, or the hippies (the film was made in 1968) but Crazy Love is much more like a punk than a hippie. There is actually a strange analog that can be made by comparing the surrealists to the dadaists and the hippies to the punks.

Both the surrealists and the hippies wanted to reform the world. Both had radical tendencies but both were also dreamy and romantic. The hippies were utopian, they believed in the wisdom of nature and love and wanted to see a world free of strife. Surrealists had a darker vision of the repressed world and the human psyche but the surrealists were Marxists and like the hippies wanted to see humanity liberated from societal conventions.

The Surrealists wanted to “shock the bourgeoisie” and the hippies wanted to “blow people’s minds” but whatever the nomenclature both movements had a romantic facet that wondered at the mystery of human potential.

Neither Dada nor punk gave a shit about human potential or liberation. They were fueled by anger, contempt, and a desire to scream at the top of their lungs. A comparison of the surrealist poetry of Andre Breton to that of Dadaist Kurt Schwitters makes the difference clear.

Andre Breton (excerpt from Always For The First Time 1934)

“Always for the first time

Hardly do I know you by sight

You return at some hour of the night to a house at an angle to my window

A wholly imaginary house

It is there that from one second to the next

In the inviolate darkness

I anticipate once more the fascinating rift occurring

The one and only rift

In the facade and in my heart

The closer I come to you

In reality

The more the key sings at the door of the unknown room”

Kurt Schwitters (excerpt from Ursonate 1932)

Michio Okabe’s film Crazy Love is closer to Schwitters and a nihilistic contempt for constructed meaning than it is to the surrealists, but there are elements of both. The film consists of pranks and stunts performed for the camera. A bunch of twenty-somethings disrupts the decorum of Tokyo’s streets by dragging each other around, or fighting on a train platform, or “cross-dressing” and twirling through the alleyways. It’s a little bit Merry Pranksters and a little bit Situationist International both of which were at their peak at the time.

Parts of the film can feel a bit adolescent, but there are some compelling ideas mixed into the mess. At one point the camera wanders around a nightclub. As it is jostled by the crowd a sinister-looking man in a suit looks directly into the camera and curling his finger signals us to follow him. The camera obeys and the man leads us outside. The camera then wanders around town with the strange man’s finger in the frame pointing at whatever the camera sees.

It’s a fascinating redundancy that reminded me of a Bruce Nauman painting that spells out “Pay Attention Mother Fuckers” in black letters painted backwards on an enormous canvas. (See below) Both the movie and the painting share a self-conscious anger toward an audience the artist is ambivalent about at best.

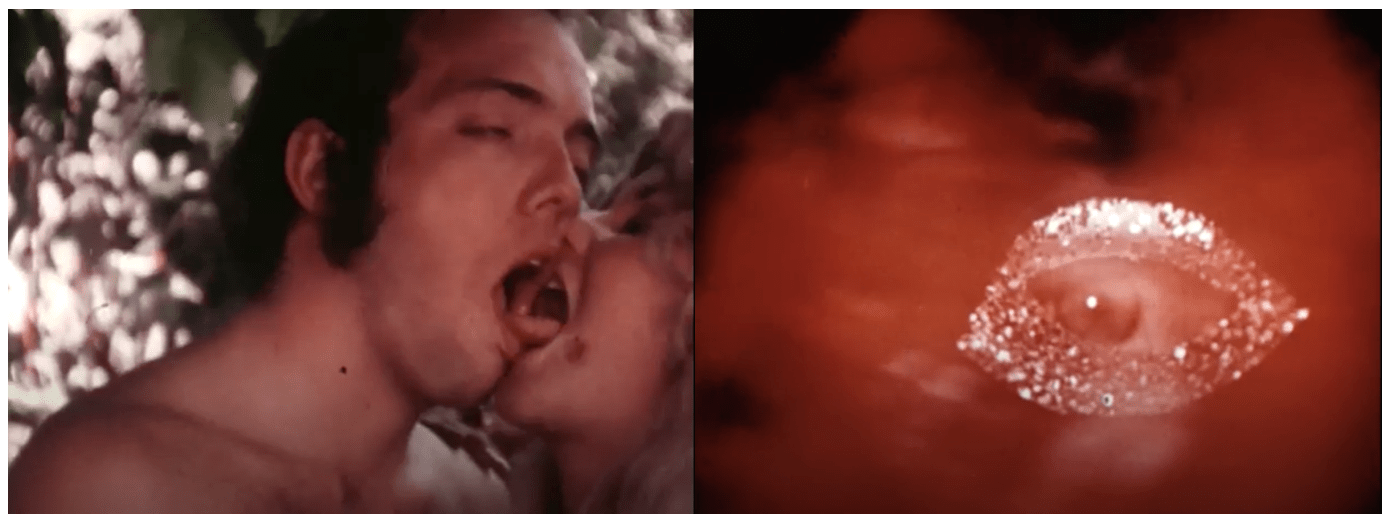

As part of their onslaught on society, the Crazy Love crew include a lot of queer content. Most of it seems like an organic outgrowth of who they are, but some seems to be performed for shock value. There is a scene where two young men wrestle in their underwear and it slowly morphs into making out. The two men seem a little tentative as if they aren’t really into each other but are trying to shock the audience.

There are however other scenes where young men and some young women seem to be expressing their genuinely queer orientations. A young man in a flamenco dress glamorously wriggles in a state of ecstasy as he dances and tumbles through the street. He is an exuberant vision of playful and unabashed queerness.

As the film progresses it gets more fractured and random. Okabe begins including pages from magazines, album covers, reportage about the war in Viet Nam and the 1968 riots in Paris. The pacing speeds up and some of the images spin around but despite the increasing intensity it all starts to blend into a tiresome, repetitive montage. There are still, however, interesting bursts of rebellious energy.

At one point the crew clumsily stage a scene from Godard’s Breathless interspersed with stills from Godard’s original film. Later they bring the camera into a functioning movie theater. The theater is in the middle of showing a Western and has an audience watching it. The Crazy Love Crew just start filming over everyone’s shoulders as if the world is theirs to appropriate.

Crazy Love has its moments of brilliance but it is difficult to keep up the fever pitch for 98 minutes. The film stock switches from black and white to color and back again. The reel is made to jump and sputter and sometimes the whole thing is upside down. Okabe tries everything to keep it going but does not always succeed. By the time it’s over it’s a relief.

1968 was a momentous and turbulent year. It was a turning point between the free-thinking optimism and creativity of the ’60s and something more frustrated and bitter that was on the horizon. It’s the difference between the hippies and yippies, between Timothy Leary and Abby Hoffman.

Okabe’s film is essentially a compilation of all these forces. It combines both mainstream and alternative culture to provide a context for Okabe’s guerrilla street performance pieces. It’s a lot to sit through but there are some compelling ideas mixed into the breathless abandon.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/situationist-international-and-thermroc