How many movies from the 1950s open with the same footage of an atomic bomb exploding? How many begin with an atomic bomb exploding followed by a quote from the Bible? I know I have seen more than my fair share, but yesterday I watched the one that started it all. Made in 1951, Five was the first movie to wrestled with life after a nuclear apocalypse.

The 1950’s began a new era. Never before had humans possessed the power to completely annihilate all life on earth. This constituted a grave shift from the days where wars were localized and survivable. During WWII many English children were simply shipped north to wait out the war while the fighting raged in and over London, but in the new atomic age there was nowhere to hide. This profound change began an age of anxiety that still persists to this day.

Five may be distinguished by virtue of it's being first but as a film it has many shortcomings.The bible passage Five chooses to open with is as follows, “The deadly wind passeth over it and it is gone, And the place thereof Shall know it no more.” The movie starts at this fever pitch of post-apocalyptic panic and then cuts straight to a bedraggled woman roaming a deserted landscape crying out, “Help me, somebody, help me, please.”

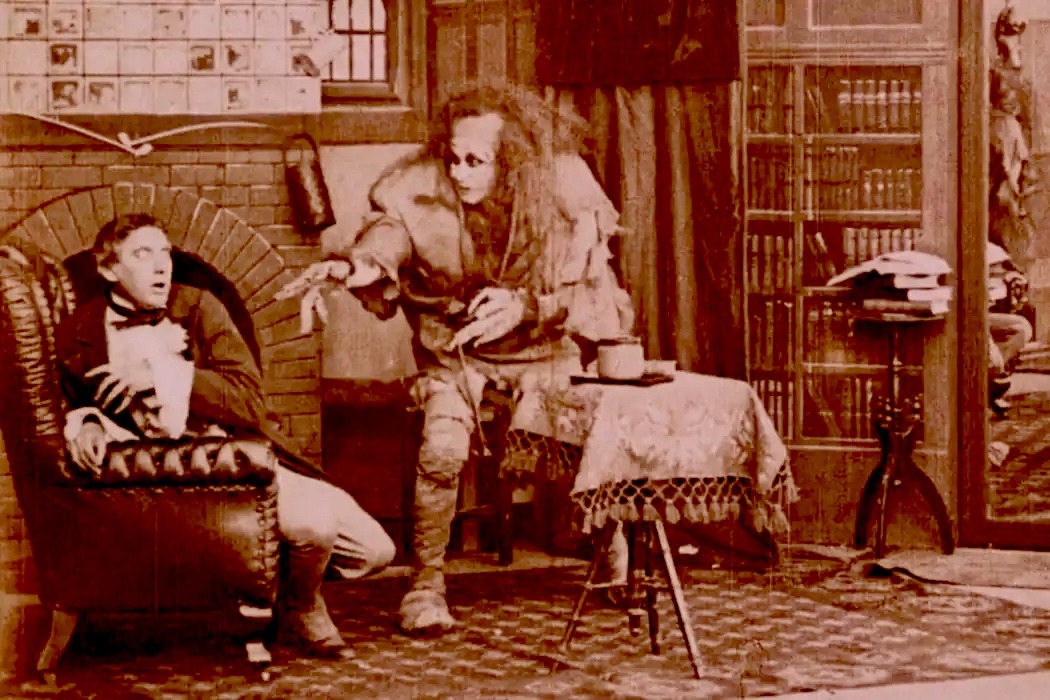

Once she finds a man (what all women need), the film slows down and the stilted dialogue begins. It’s not so much dialogue as it is a series of beat poet-style monologues. In an early scene, the woman, who is named Roseanne, is speaking with her newfound hunky guy named Michael. The conversation gets heated and Michael shakes Roseanne saying, “They’re all dead, everyone! You and I are in a dead world and I’m glad it’s dead. Cheap honky tonk of a world.”

Michael and Roseanne settle into a house in the hills and start trying to find a sustainable way to live. They are soon joined by a banker named Oliver and his coworker, a black man named Charles. Lastly, Eric washes up on shore half dead, but is soon revived. This brings the survivor headcount to five, hence the title.

They all take turns quoting the Bible and pontificating about “man". The film is a chamber play, a bit like Lifeboat or Night Of The Living Dead,except Five is boring, predictable, and stridently moralistic. The nuclear apocalypse is just a premise to bond five strangers together and apply pressure to produce drama. Actually, it’s a lot like a reality television show, but without the bikinis.

The cinematography is credited to two people, Sid Lubow and Louis Clyde Stoumen. It is probably the strongest part of the film. It mixes some shaky hand-held footage with carefully composed imagery and creative blocking. Neither cinematographer went on to make much of note, but their contribution to Five was impressive.

It was written, directed, and produced by Arch Abler in 1951. The film has a pretty dark ending where everyone’s plans and schemes for survival fail. All that remains, in the end, are Roseanne and Michael. Obler seems to feel that their survival is enough resolution to bring a close to the film. As we zoom out from the couple, another Bible verse fades in, “And I saw a new Heaven. And a new earth… And there shall be no more death, No more sorrow… No more tears… Behold! I make all things new.” First God makes a world of “death", “sorrow”, and “tears", (his words, not mine), then he kills almost everyone in a nuclear apocalypse, and now he wants to be congratulated by the survivors. Typical.

The film doesn’t bring up many issues around war, or human nature. It doesn’t have an anti-war message or express a fear of technology or modernity. It has nothing to say except that people would have difficulty getting along after an apocalypse, which is most likely true, but hardly a deep insight.

As much as Five was a product of a collective anxiety it may also have been a reflection of collective wish fulfillment. In talking about these post-apocalyptic movies a friend of mine said “We’re all unconsciously sick of modern civilization.” There are certainly enough world annihilating movies out there. From On The Beach and Dr. Strangelove to Night of The Comet and I Think We’re Alone Now. Who hasn’t wished that humanity’s grubby footprint could be washed away leaving a few good hearted people to while away their days in Eden. Perhaps part of what makes these disaster movies frightening is our secret desire to burn everything to the ground.

There are actually a variety of desires and or impulses these kinds of films can address. They could satisfy a desire to return to “a simpler time,” a desire to be the most important person in the world, a desire for revenge, or a just a desire to be left alone, but most of all they address our ambivalence toward “progress.” The future is unknown and the presence of machines, or social media or AI both excites us and frightens us.

Each time we move forward there is an uncertainty about what we are leaving behind, as well as a fear of what might be ahead. Each new building we erect requires the invention of a new Kaiju to destroy it.

The first Godzilla movie came out only three years after Five. A Japanese nightmare brought to life by the same anxieties that fueled the creation of Five, and yet we find ourselves rooting for Godzilla as he smushes tanks underfoot and chews his way through Tokyo. Over the years Godzilla’s role as destroyer has been repeatedly reimagined in ways that reflect our ambivalence toward those who might wipe the slate clean.

Movies like Five are meant to frighten us about a possible future, a future that will undoubtably be horrible and bleak, but even before the industrial revolution, humanity fantasized about the “noble savage.” The primitive, yet wise individual who lives free of all of society’s requirements and rules. A simple person who exists in harmony with nature instead of indulging in our foolish modern ways. The same could be said about the idealized American frontiersmen. A man who’s wisdom comes from working the land and getting his hands dirty.

In the event of a real all out nuclear war it would be much better to die instantly. There would be no new Eden, just a poisoned planet hostile to almost all life. However, in the myopic narcissism of our fantasies a nuclear apocalypse might be an opportunity to start over and reshape the world into what we believe it should be. Perhaps we should fear the fantasy of an apocalypse more than the possibility of the real thing.

If you enjoyed this article you might also like - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/the-27th-day-may-not-be-the-worst-movie-ever-made-but-it-might-be-the-stupidest/