The Crimson Bat series is based on a manga character created by Teruo Tanashita. There are four films in all. The first two were directed by Teiji Matsuda. The second two by Hirokazu Ichimura. Unfortunately, they are very difficult to find. The films in order are entitled:

Crimson Bat: The Blind Swordswoman (1969)

Trapped, the Crimson Bat A.K.A. The Blind Swordswoman: Hellish Skin (1969)

Watch Out, Crimson Bat! (1969)

Crimson Bat - Oichi: Wanted, Dead or Alive (1970)

Crimson Bat, Blind Swordswoman

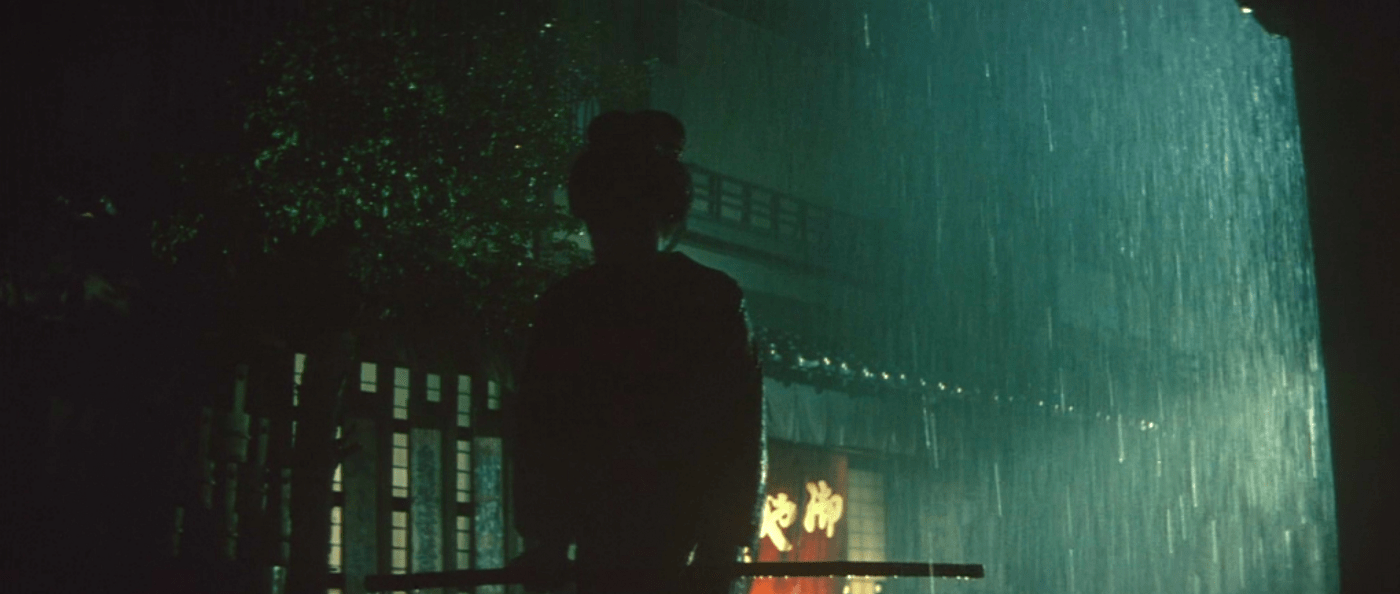

Crimson Bat, Blind Swordswoman is an amazing melange of movie styles and tropes blended with epic-scale cinematography and melodrama. It has the gory hyperbole of Lone Wolf and Cub, the swagger of a Sergio Leone spaghetti western, the trappings of a Zatoichi film, and the artifice of films like The Ballad of Narayama and Kwaidan.

The plot and the sequence of scenes are difficult to follow. The story is a byzantine tangle that is meant to tie up neatly in the end, but is too confusing to truly be coherent. Its failings as a narrative are of little consequence, considering the visual feast that is laid before the viewer. For example, the scene where our heroine, Oichi, so forcefully slices a man with her scarlet sword-cane that he flies into the air and ends up draped over a tree branch, raining down a torrent of blood like a red-beaded curtain in front of our heroine, who stands stoic, but triumphant against a darkening sky.

There are many posed moments where the screen becomes a dramatic tableau. There is a burst of violence, and then everything stops while we wait for the shocked victims to fall from their frozen poses into bloody heaps on the ground.

The references to Zatoichi and Leone are very likely deliberate. A parody of Zatoichi even makes a cameo in one scene. A group of guards is running through the streets in pursuit of Oichi when they crash into a blind masseuse, stumbling drunkenly through the street with a cane. One of the guards yells, “Get out of here, you blind masseuse!” For the uninitiated, Zatoichi was a very popular chanbara (swordplay movie) series about a blind masseuse with a sword-cane.

As for Leone’s influence, it is apparent throughout the film. There are one-on-one showdowns on windswept planes and tense face-offs in gritty gambling parlors, but it is Leone’s partner in crime, Ennio Morricone, that really leaves his mark. The soundtrack to Crimson Bat, Blind Swordswoman is spectacular. Like the film, it is an eclectic mix of styles. The majority of the music is played on a sitar, tabla, and flute. The sitar plays long sustained chords, and the tabla punctuates them with sparse clusters of tones. Above this thoroughly Indian sound floats the pentatonic lyricism of Japanese flute music. It's odd, but it works seamlessly. There are also moments when the soundtrack moves into a more Western mode with an orchestra, but at the forefront is a grimy, acid sound of an electric guitar that prowls along like an angry cat.

In addition to the chanbara story arc, Crimson Bat adds a combination of the female revenge film with the much older story of the scorned and pitiful women damned to a life of bitter sadness.

Both tropes have the potential to address feminist issues, but in many films from the 60s and 70s, the entertainment is emphasized over content. The revenge plot is often used as an excuse to show an eroticized rape scene followed by a gory revenge scene. They weren’t about power, or injustice, they were just titillation masquerading as something substantive. There are some notable exceptions, and Crimson Bat, Blind Swordswoman is one of them. There is no eroticized violence against women in it. The one rape that does occur happens off-screen.

The life of the main character, Oichi, is a life of an outcast, as is typical of all good western-type heroes, but part of her outsider status is due to her being a woman. She’s not a morally ambiguous gunslinger or a misunderstood fugitive. She is a woman who has never been recognized or valued by society. Her parents abandoned her, she is unmarried, and she is without rank or employment.

In the ideology of the American western, the gunslinger is a buffer between the good people of the farm, or the prairie, and the bad elements that need to be kept at bay. The innocence of the settlers is kept pristine, while the gunslinger does the dirty, immoral, but noble job of killing the bad guys. The gunslinger must remain an outsider because he is essentially antisocial and cannot be part of the community.

Oichi plays this role, but she was forced into it by a society that does not respect or value women. Like the victims of society that she defends, she too has been wronged, she too suffers at the hands of the greedy and unscrupulous. Unlike Clint Eastwood, she displays her pain and expresses her sympathy for the wronged. She is not a cold, steely killer with a swagger and a cigarette, but she is just as deadly.

Aside from the western trope, Oichi also represents the older figure of the wronged woman. There are many such figures in Japanese history and mythology. Such a woman is a symbol of the pain that societal obligation brings. Japan’s strict code of conduct and rigid hierarchy of position is the driving force in many of the country’s tales and tragedies. The woman wronged by the heartless man of high position, the couple torn apart by duty, the family turned against itself by tradition, all highlight the misery caused by Japanese society, while often refraining from actually challenging it.

Oichi is a woman society cannot accommodate, and so she must suffer on its margins. She cannot rise up and overturn society. Instead, she stays in the shadows and fights smaller battles. She advocates for those like her who have been placed in an impossible position by a system that has no use for them. There are hundreds of Japanese stories and legends of wronged women who are fated to suffer. In addition, there is a never-ending supply of tragic ghost stories where women who have endured injustice in life come back as vengeful demons, like Oiwa, Ubume, or Banchō Sarayashiki.

Crimson Bat, Blind Swordswoman may have been an attempt by Shochiku studios to compete with Daiei Film Studio’s Zatoichi, but it is also one among many movies from the 1960s and 70s that feature women as vengeful outcasts, such as the Female Prisoner Scorpion series, Sex And Fury, Ohyaku: The Female Demon, Blind Woman’s Curse, and The Red Peony Gambler series.

The early 70s was a time when modern feminism first began to take shape. The blending of the trapped victim with the vengeful anti-hero emerged as a popular idea. The same trend was taking place in America with films like I Spit On Your Grave, Ms. 45, and Last House on The Left. Japan’s blend included a second layer, that of the past and the future. By setting many of these films in the Edo period, they speak not only about the status of women, but the history of how that status was created and maintained.

Trapped, the Crimson Bat

The second Crimson Bat film is entitled Trapped, the Crimson Bat. It came out the same year as its predecessor and was also directed by Sadatsugu Matsuda. It is in line with Crimson Bat, Blind Swordswoman in that it draws heavily from both westerns and chanbara. However, Trapped is a more emotional film. Oichi is further developed as a character and we see her inner conflict brought to the fore.

Oichi feels as if she is so tainted by the sins she has committed that she is damned to a life of dishonor and exile. She believes that there is no turning back from the path she has chosen. She will have to keep traveling from town to town her entire life and work as a lonely bounty hunter, unfit for society.

She, however, meets up with an earnest and sincere fisherman, who loves her and accepts her, even after finding out what she does for a living. They have several emotional exchanges and Oichi begins to let her guard down. His unconditional love helps to open her up to true intimacy.

Her open heart allows us to see the true nature of the price she has paid for both hardening and hating herself. Clint Eastwood never experienced awakenings such as this. The second half of Trapped begins to feel a little more like a noir film. We have a heroine who wants to leave the dirt and sin of the streets, but the streets will not let her escape. As Michael Corleone said in Godfather Part III: “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!” Hence the title Trapped.

Oichi’s antagonist is Oen, a woman who has given herself over to the life of criminality, manipulation, and cruelty. To Oen, Oichi’s inner conflict is simply a weakness. Oen’s weapon of choice is her whip. She explains its nature to one of her victims and provides just a small window into her own motivations. “This [the whip] is made from women’s hair. Once it curls around you, you can’t get away. The hate of jilted women is woven into it.”

Oen is again a nod to the vengeance trope and women’s desire to finally be in the dominant position.

As the film progresses, it becomes more stylized and operatic. The emotions become melodramatic and everything is brought to a grandiose climax. The final bloodbath happens in a sun-scorched, rocky ravine, but as it progresses, it becomes increasingly more stylized. By the end, it is taking place in front of a rear projection screen, rippling with waves of light while all else is dark. Eventually, the editing is reduced down to a quickfire montage of film stills and blood splatter.

Watch Out, Crimson Bat!

The third film, Watch Out, Crimson Bat! was directed by Hirokazu Ichimura. Unfortunately, Ichimura does not do a very good job at all. The cinematography and compositions are far less baroque and are instead ordinary, utilitarian arrangements, with the action in the middle and the key light on the subject. The theatricality and artifice are gone, and we are left with something far less creative.

In all four of the films, the plots are somewhat standard. They follow a spaghetti western structure. There is also some of John Ford’s sensibility in that there is a lot of sympathy paid to the honorable farmers trying to hold on to the simple and pure ways of the ordinary man, while the cattle rancher, railroad tycoon, or oil baron tries to force modern capitalism down their collective throats.

All of these tropes are fine, but without some style or originality, they just feel flat and routine. Watch Out, Crimson Bat! adds nothing to Oichi’s character or development. The film simply coasts on the momentum of what came before it. We take for granted that Oichi will side with the meek. We know she will earn people’s admiration, but she will make no friends. We know she will walk off into the distance alone.

Both the second and third films have a lot of similarities to George Stevens’ 1953 western Shane. There is the same hired gun who comes to kill our hero. There is the same limited role that our antihero is willing to play. In Watch Out, Crimson Bat!, the ending includes Oichi exiting the film on a long dusty road while a young girl calls after her in vain.

The sitar and acid guitar are gone. They are replaced with a more conventional orchestra. The garish soundstage backdrops are gone, and so are the bright pops of color and deep contrast of shadows. It doesn’t live up to its predecessors, and on its own, it's ordinary at best.

Crimson Bat - Oichi: Wanted, Dead or Alive

It is immediately apparent that the fourth movie, Crimson Bat — Oichi: Wanted, Dead or Alive is much better than Watch Out, Crimson Bat!. The opening music begins with that same acid guitar from the earlier movies, nasty and distorted. Then the guitar is joined by a western-style classical flute. Then both instruments are replaced by an accordion. It’s strange, unexpected, instrumentation that bodes well for a creative journey.

After the first fight scene is over we are treated to a brief but properly cinematic scenario. We see a wanted poster and then a crowd around it gossiping over the reward. A classic trope, but then we cut to a man on a horse swinging a kama (sickle) on a chain. He comes charging through and just as you think he is going to attack the defenseless villagers he whips the chain around the post with the wanted sign, rips the entire signpost out of the ground, and rides off with it. Now, that is a cinematic way to grab a flyer.

Then the familiar elements are set up. This time it's the magistrate who plays the heavy. He wants to install a new port to promote big business and needs the local fisherman to clear out. Besides this central conflict, we have the continued tension provided by Oichi being a fugitive from justice. The poster from earlier was of her. Without her doing anything she already has a motley clutch of bounty hunters in hot pursuit, but of course, she gets embroiled in the central plot between the fishermen and the magistrate as well.

The film returns to a more personal arena that was lost in Trapped. Oichi continues to struggle with her desire to escape her outsider status and settle down, but the theme is expanded by several insightful depictions of supporting characters around her. The salient theme that emerges is characters finding their purpose. It's reminiscent of the Bhagavad Gita in that an individual’s purpose is not entirely within one’s control, and it may lead to tragedy, but the fulfillment of that purpose is the only correct path. The morality of your choices is secondary to being who you are supposed to be.

The fight choreography in the first two films was mannered and dramatic. Realism was traded in for arresting poses and gestures. The choreography in the third film was poor. The moves were unconvincing, undramatic and the blood was badly applied. This last film manages better fight scenes. We get a fight in a thunderstorm, and a fight in the middle of a fire. The moves are not perfectly believable but they are much better.

One of the most important features in any fight scene is the number of edits. In Psycho, Hitchcock had 52 edits in his shower scene, but it was not a fight scene. It was a one-sided murder where we were meant to be as confused, disoriented, and terrified as the victim. The more edits you have, the more control you have, but breaking a fight scene into tiny bits can completely destroy the action.

What made the Hong Kong kung fu films so amazing was their sparse editing. The actors weren’t just actors. They were trained experts in kung fu who could really go at it. All the camera had to do was follow them. Hong Kong films were notorious for getting actors hurt, but the result was a compelling and visually engrossing fight scene.

None of the actors in Crimson Bat - Oichi: Wanted, Dead or Alive were trained swordsmen, although they most likely had teachers and consultants. The fight scenes may not have been that believable, but they weren’t edited to death and so successfully generated tension.

Oichi meets many men in her travels, and each movie features a dutiful samurai contrasted against a mercenary samurai. Often, both samurai start off as Oichi’s enemy. Then halfway through the film, after a few fights, the dutiful samurai recognizes Oichi’s strength of character and superior sword skills, and warms to her. The samurai’s honor and sense of duty allow him to align himself with her. In Crimson Bat - Oichi: Wanted, Dead or Alive, the good-hearted samurai is named Sankuro, although I like to think of him as Mr. Eyebrows. He’s a hunky guy, fierce with a sword, but has a soft heart under his kimono. He is also a bit of a philosopher and helps flesh out some of the themes in the film.

Here is a dialogue between him and Oichi. Oichi reproaches the samurai for not following his true path of being a doctor and helping people. Sankuro answers, “What have you become by helping men? You’ve become a fugitive. Are you satisfied with that? Are you happy as a woman?” Staring off into the distance, Oichi answers, “I don’t know. I don’t aspire to such great deeds as helping people. But there are people who are bullied and trod on. I’ve been bullied too.” The scene and the dialogue are reminiscent of Henry Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath. An admiration for the laborer and a disdain for their oppressor permeate both films.

Oichi continues, but sounds more like a noir detective again, “Someone tries to kill me, my sword comes out by itself. I feel warm blood on my skin. I hear a thud when the body falls. After that, I feel nothing.” Sankuro and Oichi embrace and continue talking, and then Oichi calls out, “Don’t. Don’t hold me. No man who loves me can be happy.” It's a familiar melodrama, but when its well played and in the right context, it is still compelling. The whole scene is set to the vibrating chords of an accordion.

All four films have an air of self-awareness. They draw from familiar sources and invigorate those sources, not only with a switch of gender, but with a unique combination of elements. It's a familiar recipe, but with different proportions and different techniques. The result is something new and unexpected.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/two-film-adaptions-of-botan-doro-japans-favorite-ghost-story