Currently, western culture embraces the tenets of multiculturalism. There is a desire to recognize all cultures and ideologies as worthy of respect and to see humanity’s diversity as a rich resource. Omo Child presents a troublesome case that challenges the limits of multicultural optimism.

As a whole, The West has been able to accommodate substantive and profound differences within the multicultural world but can it accommodate a tribe of people who frequently kill their children? In the Kara tribe in Ethiopia, men are allowed to have multiple wives as well as “girlfriends.” If a woman gives birth out of wedlock that child is deemed a “mingi” and must be executed. If a “girlfriend” gives birth to a child her child will also be deemed a “mingi” and executed. Lastly, if a child’s first teeth appear on the top of his or her mouth instead of the bottom, this child too is a “mingi” and must be put to death.

The justification for this practice is that it is an “ancient tradition” which keeps the Kara tribe safe. If the Kara were to allow these children to live they would bring grave misfortune to the tribe. One of the elders (the authorities in the tribe) explains, “The mingi children must be killed because if you don’t the pure Kara, will die.” To a westerner, the word “pure” is a frightening red flag indicative of a dangerous mindset. Of course, the elder who said this is unaware of eugenics or white supremacy, but this makes him all the more dangerous.

Tradition is a word that lends an air of importance to whatever it is applied to and yet it indicates nothing more than a practice that has been done before. The word tradition transforms simple conformity into something valuable. If you ask “why do you kill children?” And the response is that it is an ancient tradition, this lends the practice the gravity of something culturally significant. If on the other hand, the Kara were to justify their murders by saying “I am doing this because someone else did.” The answer is qualitatively the same but sounds unfounded and irrational.

The documentary Omo Child was made in 2015 by a white American director John Rowe. There is an unfortunate history of white men observing African traditions with a disapproving eye. Christians were horrified when they first witnessed the “ungodly” behavior of native Africans. So too the Muslims. Both religions conquered large swaths of the continent and brutalized the inhabitants until they worshipped the “correct” god in the “correct way.” The countless western invasions and atrocities cannot just be set aside by saying, “Yes, but this time the West is clearly right and the Kara people are clearly wrong.” This may well be the case but there is a historical context that can not be ignored.

John Rowe did not spearhead the movement to end the practice of mingi, but in this film, he is documenting the controversy. Though Rowe is far from neutral, he is comparatively less political than the direct agent of change represented in this case by Lale Labuko. Lale was a full-blooded Kara tribe member, but his father sent him away as a child, to get an education. This was forbidden by the Kara elders. After completing his education, Lale felt compelled to return and to try to ban mingi, a practice to which he had lost two sisters. With one foot in the West and the other in the tribe, Lale had a unique position and identity. Through his deep love and respect for the tribe was his professed motivation for advocating against mingi, his Western education becomes evident when he refers to the practice as “barbaric.”

The heart of the film is observing the interaction between Lale and his tribe as they navigate explosive territory. It’s a tense film, a painful film but the journey is compelling. Everyone is given an opportunity to present their case to each other and to the camera.

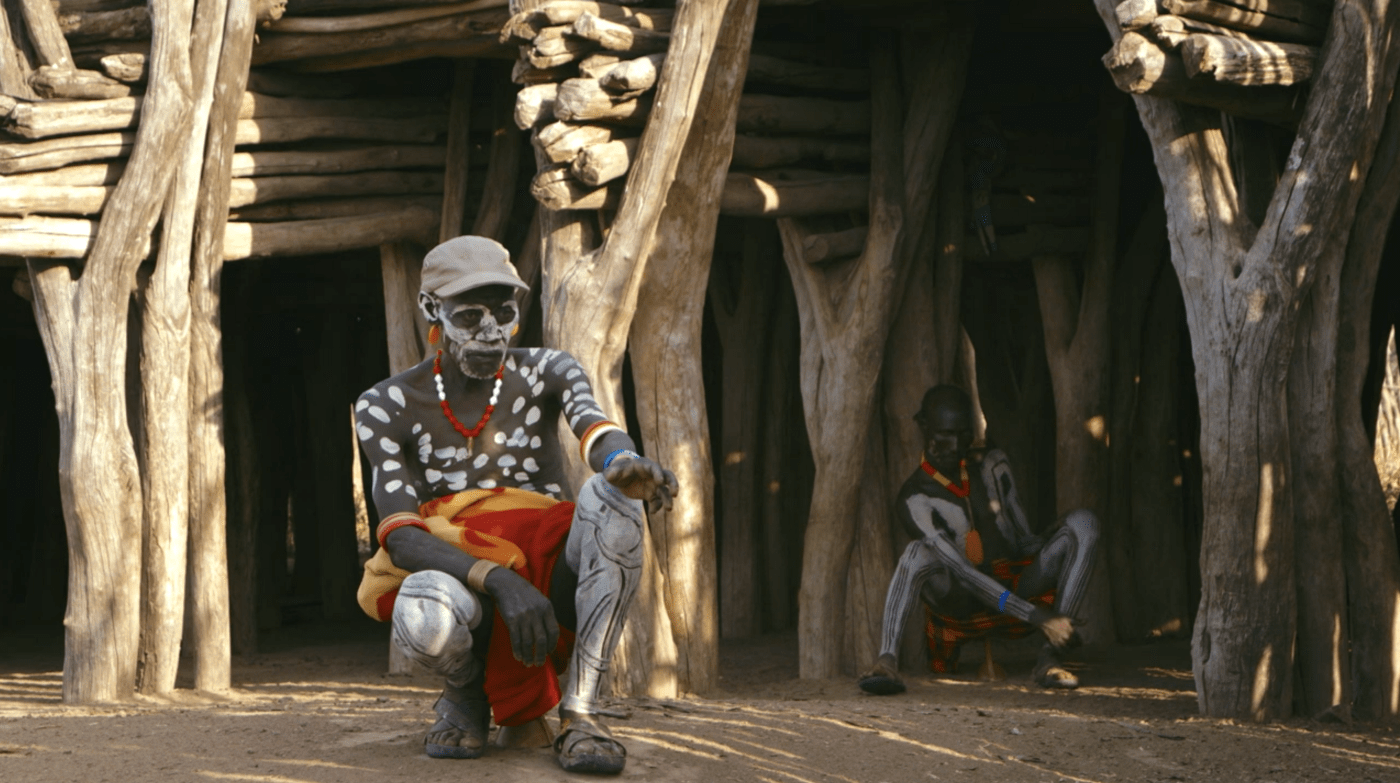

The film is visually beautiful. The people, the landscape, the village, and animals are all rendered in high definition, brightly colored, splendor. The gorgeous imagery provides a strange juxtaposition to the grave matters they are discussing.

The film presents us with one instance of what happens when western culture comes knocking, however, the issue of assimilation is a potent and driving force all around the world. The space between peoples continues to shrink. An increasingly mobile population and global economy draw us all closer. These issues will remain at the forefront for years to come.

In addition, the problem will accelerate as climate change rapidly makes large areas of the globe uninhabitable. Entire regions in Africa and the Middle East will be forced to relocate and cultures will continue to clash. The question becomes who will negotiate these conflicts, and on whose terms?

Rowe’s documentary ends by telling us that there are still 50,000 people in Ethiopia who continue to practice mingi killing. Issues such as these abound. The World Health Organization estimates that 200 million women have had their genitals mutilated in countries all over Africa as well as Indonesia, Iraqi Kurdistan, and Yemen. If you call it genital mutilation it sounds horrifying if you call it female circumcision it sounds acceptable. There are those in the west who look upon male circumcision as genital mutilation. The United States Centers for Disease Control estimates that 55% to 65% of Americans have undergone the procedure. There are groups around the world that fall on either side of both male and female genital mutilation.

Whatever the goals of these conflicts are, what matters is who arbitrates them. There is no neutral position and there is no neutral arena. Culture is not a force that exerts influence on us from outside. It is part of what creates us, from our sense of self to our understanding of where we belong. What you see when you watch Omo Child will largely be determined by what you see when you look around you. There is no direct way to untangle the web of differing moral systems but inaction is as much a choice as action.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/tanna-a-reenactment-of-culture-change