Considering the iconic status Godzilla already had in the 1960s it would have been intimidating for any director to be tasked with making the next film in the series, but when Yoshimitsu Banno was picked for the job he had never even made a feature film before. Godzilla vs. Hedorah was to be his first. Not only that but he would have to show the rough cut to Ishirō Honda, the originator of the Godzilla franchise, for approval.

Many a director might be hesitant and play it safe by creating a pale and tentative imitation of his predecessor’s work, but when Banno got the job in 1971 he definitely did not hold back. Godzilla vs. Hedorah was a bold departure from past Godzilla films. It did fairly well at the box office, but Banno’s drastic changes were enough to get him fired anyway. He was scheduled to make more Godzilla films but the arrangement was canceled.

Banno’s departure from the norm begins right from Godzilla vs. Hedorah’s opening credits. The screen comes to life with psychedelic colored oils splashing and sliding past each other. A woman appears and begins to sing a funky 1960’s sounding pop song. Then interspersed with the psychedelia come morbid flashes of pollution and man-made disasters. Banno sets up a fast-paced and almost free-associative style.

He throws in a strange variety of formalist flourishes. He chooses random moments to suddenly switch from live-action to animation. The cartoons are based on the film but are not part of the plot. Sometimes they are just a kind of riff on what is going on and other times they are didactic little inserts of extra information delivered in animated form. When Professor Toru Yano explains nuclear fusion to little Toru Yano we get a School House Rock style cartoon illustrating the professor’s lesson.

The plot of Godzilla vs. Hedora is still standard issue. A beast from space surfaces out of the ocean, where all beasts from space live, and begins to wreak havoc on Tokyo where all Japanese people live. Kaiju are always made stronger by some new “modern technology” that we humans are being irresponsible with. In Hedora’s case, it is smog and pollution produced by the spread of industry.

Little Toru is a know-it-all little boy in very short overalls who seems to understand the motivations of both Godzilla and Hedorah. The sober scientist is his father who figures out everything in little test tubes. At one point, when the scientist is hard at work theorizing, the film cuts to a shot of Rodin’s Thinker steaming in the sun. It’s just a quick cut, that functions as an illustrative footnote of free association.

Godzilla himself is different as well. He has picked up certain mannerisms as if he had been watching Bruce Lee movies. When facing off with Hedorah he nods his head, wipes his mouth, and pumps his arm, as if to taunt his opponent. At one point Toro even imitates Godzilla, highlighting this strange new mannerism.

As is typical in Kaiju films the fight scenes are slow and awkward. Godzilla and Hedora mostly just stand there and yell at each other. Godzilla has his trademark roar which is fine but it sounds to me like they only had two different recordings which they relentlessly play on a loop. The fight scenes may be slow but Banno manages to throw in some surprises. There is a shot from Hidorah’s point of view as Godzilla leans in to wallop him. Godzilla also gets an odd wide angle close up as seen below.

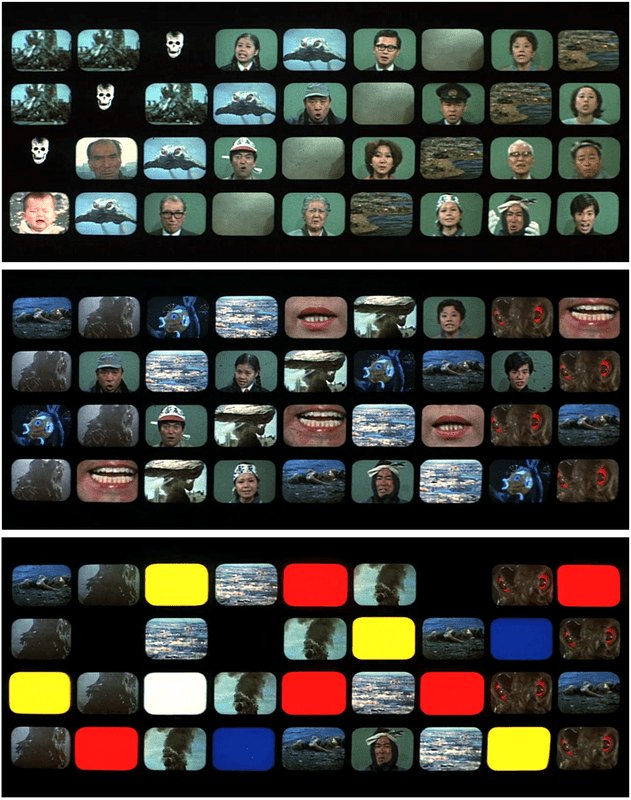

Before the climactic fight begins there is a crazy crescendo of frantic yelling and activity as Banno cuts to different locations and different moments in the film. He splits and resplits the screen until he assembles a giant grid of flashing images. Some of them just flash skulls, others are newscasts or footage of Hidorah. It culminates when all the squares turn into flashing primary colors.

The closing of the film is just as strange. We have the typical Shane ending with Godzilla walking away into the sunset and the little boy calling after him, but then out of nowhere the film cuts to a closeup of Hokusai’s woodblock print of the wave. Then back to Godzilla and then to the wide shots of sludge and pollution. The only connection I can figure out is that Hokusai’s Wave represents Japan’s glory days before all the pollution and including it in the final montage is a way of mourning what has been lost.

Godzilla movies always center around the fear of modernism. There is a concern that industrialization will be the downfall of Japan or humanity in general, but along with this fear comes a faith in science and indirectly in nature. It is always the scientist who saves the day and restores the natural balance of forces.

Banno’s version hits all the same notes as the other Godzilla films but it definitely sticks out from the rest. Banno’s film is openly self-conscious, formal, and artificial. He tells a Godzilla story while simultaneously embracing the psychedelics and experimental spirit of the 60’s. He loved the way Godzilla vs. Hedorah turned out and was all set to make a sequel, but it was not to be.

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/latitude-zero-come-for-the-costumes-stay-for-the-pansexual-sm-subtext

[…] legacy of Godzilla began in 1954. The history of this still ongoing franchise has been divided into a variety of […]

[…] Japanese Kaiju movie that seems to target very young children, even younger than films like Son of Godzilla from 1967. Daigoro vs Goliath is a cutesy comedy with jokes that are punctuated by muted trumpets […]