I was unfamiliar with Nobita and Doraemon when I first went to watch Nobita's Three Visionary Swordsmen. I recognized the image of Doraemon, he pops up everywhere in Japanese media. He’s been around since 1969 and has made an indelible mark on the country’s psyche.

Nobita was originally a manga, and as its popularity grew, it went through the standard metamorphosis from comic book to television anime to feature films. Originally, Nobita was meant to target children ages 5 through 10, so it was all the more surprising when Nobita's Three Visionary Swordsmen turned out to be richly layered with different psychological ideas about childhood, fantasy, addiction, sexuality, morality, and identity. I’m not sure how much of it is intentional, but the movie has a variety of substantive themes for adults to wrestle with. It has been banned in China, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. I’m not sure how meaningful that is, it’s not hard to get banned in those countries, but there is definitely more to Nobita and his cat robot named Doraemon than meets the eye.

Just to get a brief synopsis of the overall premise out of the way, I grabbed a succinct summary from Wikipedia…“Nobita Nobi is a ten-year-old Japanese schoolboy, who is kind-hearted and honest, but also lazy, unlucky, weak, gets bad grades, and is bad at sports. One day, a robot cat from the 22nd century named Doraemon is sent back to the past by Nobita's future grandchild, Sewashi Nobi, to take care of Nobita so that his descendants can have a better life. Although Doraemon is a cat robot, he has a fear of mice because of an incident where robotic mice chewed off his ears. This is why Doraemon lost his original yellow color and turned blue, from sadness.”

The premise immediately sticks out as atypical, particularly for Japan. Nobita has so many shortcomings, and yet he is our point of entry, we are meant to identify with him. Then, there is his strange sidekick, who has such a maudlin backstory that he ends up blue from sadness! This is not an ordinary children’s anime. The simplicity of the drawings and the cutesy voices make it seem like it’s for the same demographic as Barney in America, but Barney isn’t purple because of some tragedy that plagues his psyche.

Nobita and Doraemon belong to the isekai genre. Japan has a very detailed and elaborate genre system for most of its entertainment. Consumers know what they are paying for when they shop in a certain genre section. There are different comics, television shows, movies, and books that target different age groups, genders, and sexualities, and it can get very specific. It’s not enough to label something sci-fi, it has to be sub-categorized into how much violence is in it, and whether that violence includes blood, and if there are robots in it or not, and whether or not it has female characters, and whether those female characters are girls or giant-breasted sex objects, and on and on. Each additional qualifier is a window into what is often a vast sub-genre. It reminds me of a time when I went into my local video store (ask your dad what those were), and I walked up to the clerk and asked, “I heard that there is a movie with Nazi zombies goose-stepping on the floor of the ocean. Have you heard of it?” He smiled warmly and answered, “Oh yeah, underwater nazi movies, which one?” I cocked my head in confusion, and he said, “Well, there are a bunch.”

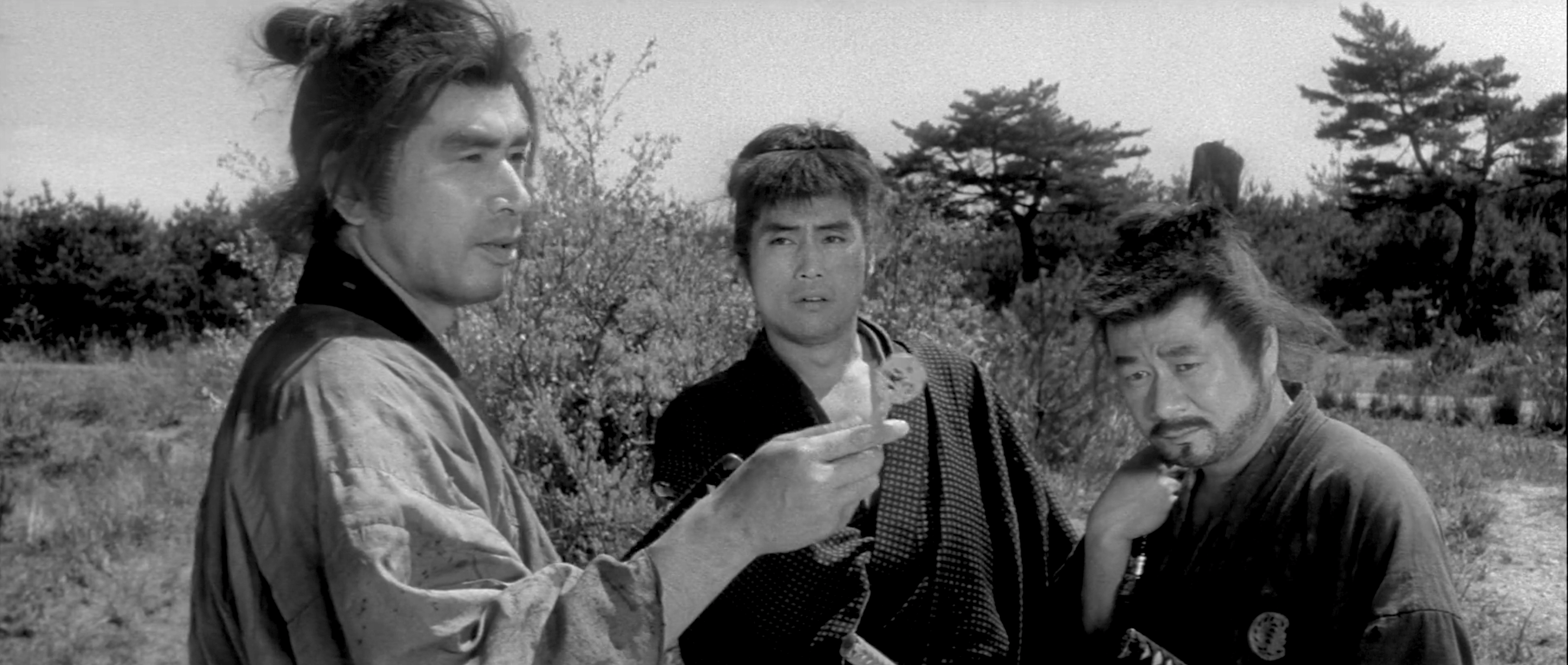

The isekai genre is a hero’s journey formula which is always set in an alternate world. “Isekai” translates to “other world”. Western equivalents might be The Wizard of Oz or The Matrix, but in Japan, it can get even more specific. Most isekai involve a hapless, bumbling protagonist who is a failure in the real world, but finds success and fulfillment in the alternate world. This is what Nobita's Three Visionary Swordsmen is. Nobita is a nerd with big glasses who constantly seems to disappoint everyone, like his mother, his teacher, and even his pet robotic cat Doraemon. His classmates are bewildered by Nobita, and for good reason. Nobita is unable to discern his alternate world from reality.

He travels to his fantasy world when he dreams at night. In his fantasies, he is joined by his classmates as they go on adventures with magic swords and dragons. He has a crush on a female classmate named Shizuoka who is always the princess in need of saving. When he runs into her, or the other children from his dreams, the next day at school, he often expects them to know what happened in his dream last night, and when his friends are surprised by his bizarre questions, he is forced to remember that they do not share his dreamworld. This always ends with the children teasing Nobita for being strange.

This setup is not so uncommon in film and literature, but in Nobita's Three Visionary Swordsmen (NTVS), there is a heavy melancholy that feels strange. Partly, it feels out of place in a cartoon for 5 or 6-year-olds, but it’s also the level of investment that Nobita exhibits in his fantasy world. He is desperate to return to it each evening, and becomes increasingly focused on controlling it.

Since Doraemon is a robot from the future, he can access all manner of sci-fi gadgets. He brings Nobita a dream machine and a library of cassettes. The cassettes enable Nobita to choose from different themes to guide his dreams. Nobita tries a few different ones and settles on a story where he is a knight in silver armor. The adventure is fine, but he is disappointed the next day, when he is unable to share the experience with the school friends who adventured with him in the dream.

To remedy this, Doraemon gives Nobita a little red button that looks like a bindi to put on his friends' foreheads. The bindi will cause them to share Nobita’s dreams and remember everything the next day. This thrills Nobita, but the other children are bewildered and exhausted the next day in school. Nobita’s fantasy life begins hurting his classmates. Predictably, Nobita sinks deeper and deeper into his fantasy world and begins to withdraw from the real world. He spends every spare moment sleeping next to the dream machine in his room so he can continue his adventures.

Then, things get really strange Norbita complains to Doraemon that the adventures are too prescribed. He wants them to be more real. Doraemon warns Nobita that the way to make his adventures more real is to lessen his control over them. The fantasies that had been adhering to formulaic genre tropes would have to become less predictable. Nobita tries it out and finds that having less control does make it more real, but it also makes it less fun. This strange zero-sum game creates a complex commentary on children’s play and imagination, not something you would expect in a cartoon for little kids.

Nobita continues to insist on more intensity, and so Doraemon reveals a special red button on the dream machine that will transpose the fantasy world with the dream world. Nobita agrees and dives back into the fantasy. Nobita’s conflicting desires and increasingly tenuous hold on reality start to feel less like an escapist fantasy, and more like dissociation, or even psychosis. He is spiraling out of control and doesn’t consider the consequences of his actions for himself, or his friends. Once in the transposed world, if Nobita and his friends are killed by any of the monsters or antagonists, they will die for real.

It all starts to resemble an addiction. Nobita is set on finding an increasingly more intense experience and must risk his life, and possibly his friends' lives, in order to achieve it. The film hints at this darker interpretation, but in the end, Nobita is able to beat the bad guys and almost win the girl, without facing any consequences for his obsession.

Doraemon: Nobita's Three Visionary Swordsmen was directed by Tsutomu Shibayama in 1994. Shibayama directed 22 of the 44 Doraemon feature films. It’s hard to overstate the impact of Doraemon in Japan. Just the films alone have raked in $1.7 billion (U.S. dollars). That’s not to mention the never-ending torrent of Doraemon merchandise, like Doraemon instant ramen, Doraemon bikinis, or the Doraemon potty trainer for boys, where you get to pee into his mouth. Then there's the TV show with over 2,000 episodes, and the manga with 1,345 separate stories. It’s shown in 60 countries. Apparently, it’s super popular in India and Viet Nam. As an American, I had seen Doraemon’s face before, but I had no idea that this little robot cat had conquered the world.

If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy this - https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/crayon-shin-chan-the-hidden-treasure-of-the-buri-buri-kingdom/