When it was released in 1992, Bewaffa Se Waffa was not a big financial success. It seems audiences didn’t like the actor who played the lead character Aslam. I can see that one might criticize him for being a little bland, but the entire film is played at such a fever pitch of operatic emotion, his more muted performance is a bit of a relief. Despite the film’s tepid reception, I found that Bewaffa Se Waffa has quite a lot to offer. It encapsulates some of the social and political issues unfolding in turn-of-the-century India. [That is my first time using “turn-of-the-century” to refer to the transition from the 20th to the 21st century. I feel so old]

The film takes place in Goa, a small southwestern state in India. The setting is of particular importance, so it is worth inserting a brief geographical summary. Goa has the fourth lowest population of all the states in India, but the highest per capita GDP. Its history, like much of India, is an unfortunate litany of one colonial invasion after another, but when the British came knocking, they were unable to take control. The Portuguese got there first and ruled it long past the dissolution of The British Empire, all the way until 1961.

India, including Goa, is one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world. There are 22 different languages and more than 2,000 different ethnicities practicing an endless number of different religions. The term “Hindu” is an umbrella term encompassing thousands of different practices. In ancient times, Goa was mostly Buddhist, but in the year 900, the Muslims came and slaughtered them all. Then the Portuguese Catholics came and drove out the Muslims, and eventually the Hindus came and tried to take over. Each group left behind living roots that eventually grew into a thoroughly heterogeneous population. The modern population of Goa is 66.1% Hindu, 25.1% Christian, 8.3% Muslim, and 0.1% Sikh.

Bewaffa Se Waffa is set in Goa because Goa’s history has produced a unique blend of cultures that set it apart from the rest of India. One issue, in particular, is polygamy. Polygamy is illegal in every state in India, except in Goa. A man may marry up to four wives in Goa and the marriages will all be recognized by the local government. As soon as he steps out of Goa and into India, his marriages are no longer valid, but as long as he stays within Goa’s borders, polygamy is permissible, if you are a man.

The controversy over polygamy in India has a long and turbulent history. Many Hindus disapprove of the practice and blame Muslims for bringing it to India. There are, however, examples of polygamy in Indian history and mythology that predate the Muslim invasion. Bewaffa Se Waffa wrestles with this heritage and openly questions the pros and cons of its practice.

At the center of the film are Aslam, Rukshar, and Nagma. Aslam is a handsome young man who happens to cross paths with Nagma and her friends in a park. Before he even speaks a word to her, he falls madly, deeply, passionately in love with her. He reveals this to her and she demurs for about 24 hours, and then falls just as deeply in love with him as he is with her. This is pretty much par for the course in Bollywood musicals. A deep and everlasting relationship of love, loyalty, and dedication is founded entirely on a brief evaluation of outward appearances.

One could argue that it is a matter of narrative expediency. The filmmakers don’t have time to show the intricacies of how two people become intimate partners, but Bollywood movies are anywhere from 3 to 6 hours long, so time is no excuse. It’s more likely that the depiction of the characters and their motivations are somewhat shallow because they are meant to be larger than life. Getting to know the characters as three-dimensional people with their own motivations and worldview would rob them of their mythic universality. The story is meant to have a timeless, "written-in-the-stars" quality. The characters are beautiful beyond compare, and their love is deeper than any love that has ever existed.

The song the couple sings when they first meet celebrates their mutual admiration and takes place in a wonderfully colorful fantasy world full of giant roses and floating veils. Less than ten minutes later, a second musical number bursts onto the screen as the couple get married in a lavish, marigold-covered wedding ceremony.

The newlyweds tumble into each other’s arms, but soon after the honeymoon, Rukshar turns out to be infertile. She so loves Aslam and his family, she begs Aslam to take a second wife so he can produce heirs. Everyone takes a turn singing mournfully about Ruksher’s request. Aslam begs her to forget it. Aslam’s father, Nawab Khan, who had so looked forward to becoming a grandfather, is also horrified and forbids it. Personally, I think he should have spent less time worried about his daughter-in-law and more time trying to fix the ridiculous grey perm.

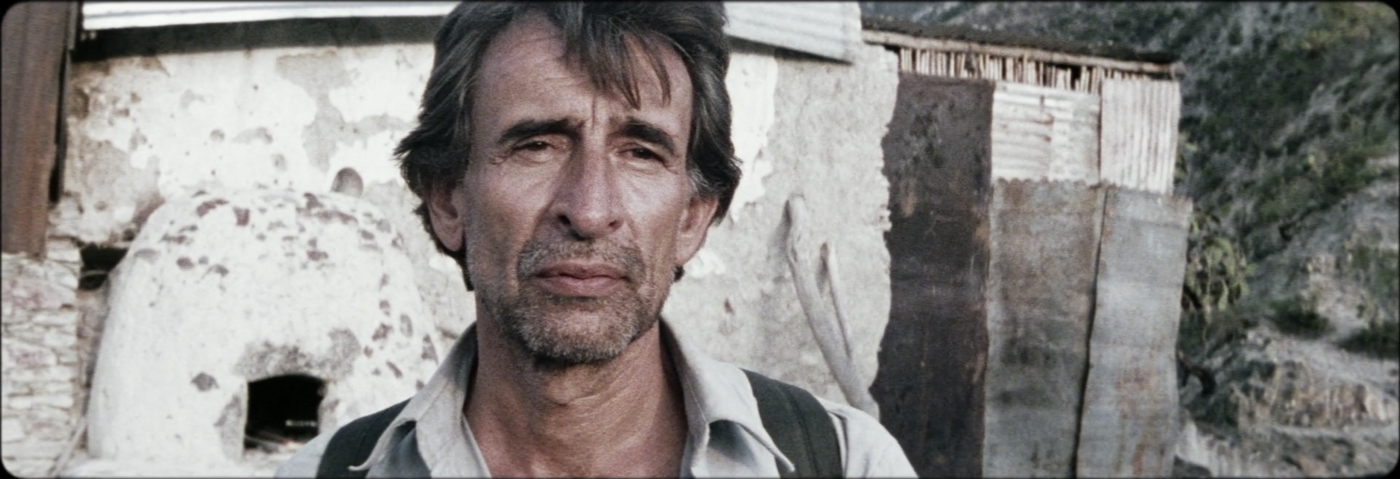

But Ruksha is undeterred. She secretly enlists her best friend Nagma to seduce the clueless Aslan while he is away on a business trip. For someone so completely dedicated to his marriage, Aslan falls for Nagma pretty quickly. In no time at all, the throuple is petitioning their respective parents to allow a second wedding. Nawab Khan (played by the famous Pran Krishan Sikand) is ready to concede to the union, until Nagma’s parents lay down some conditions. They want a contract signed that will make sure that all of Aslam’s fortune will go to the child Nagma produces. The contract alarms everyone, especially Nawab Khan, but after a long and heated argument, everyone signs it. Aslam marries Nagma, and soon after, she becomes pregnant.

Nagma’s parents pay a visit and insist that allowing the pregnant Nagma to live in close proximity to the infertile Rukshar is bad luck and will cause Nagma to miscarry. Clearly, this is a plot to separate Aslam from his first wife long enough to cement Nagma as the preferred wife.

Despite everyone clearly seeing what Nagma’s parents are doing, everyone agrees to leave poor Ruksha home alone while Aslam temporarily moves into Nagma’s house.

The forsaken Rukshar sings a sad song worthy of a romantic Italian opera. She weeps and throws herself on her bed lamenting her fate, but accepting that propriety demands it. Clearly, Nagma is not the friend Ruksha thought she was, but the pious and patient Ruksha would never speak ill or even question Nagma and her family.

Before Aslam leaves, he has a little last bit of nookie with Ruksha, and even though a dozen of the best doctors in India proclaimed that she would never have a child, she magically becomes pregnant. So now Aslam has two wives, both with a baby on the way.

I’m not going to relate the entire plot, but I wanted to convey the wonderful soapiness of the tangled web they all weave. At least, it is wonderful and soapy during the first hour and a half, but the second half of the film is very different. The second half is dark. Very dark! Like German dark! I have never seen a Bollywood film depict such cruelty and suffering.

Usually in a Bollywood musical or in an American soap opera, the villain does something cunning and nasty that causes our protagonists to suffer terribly, but the suffering only exists to make the justice of the ending feel triumphant. Typically, by the end of the film, the devious secrets of the villain’s plan are exposed, everyone shames him or her, and the misunderstood protagonist is vindicated. The enjoyment of the final triumph is proportionate to the pain the protagonist had to endure, but there is a delicate balance that needs to be struck. If the villain succeeds in inflicting too much pain, the joy of justice is ruined.

This paragraph contains spoilers. In Bewaffa Se Waffa, Nama’s father Ajgar Khan is the villain. He kills Rukshar’s father and her newborn baby. He uses lies to get Aslam and her Nagma to turn against her, he uses lawyers to con Rukshar out of all her money and inheritance, and leaves her completely traumatized and broken. There is no coming back from that. There is no punishment that the villain could possibly suffer that would bring the healing relief of justice to the situation. After all the shootouts and fistfights are over, all we are left with is a few brutalized survivors, one of whom ends the film by committing suicide in poor Rusher’s arms. Note the last frame down below.

Certainly, Ajgar and his scheming wife are to blame for the lion’s share of the trouble, but the film presents us with other contributors to consider as well. As Rukshar herself notes, none of the troubles would have happened if Rukshar had stayed in a monogamous relationship. Although the film questions polygamy, and polygamy is a Muslim practice, the film is clearly supportive of Islam. All of the characters are devout Muslims, save for the villain. We see the characters pray and periodically thank Allah. Our heroine is very religious and is likened to an angel, but the film still manages to carefully raise some difficult questions about patriarchy and polygamy. The film does not simply dismiss these issues as wrong. Instead, the film develops a complex plot that highlights a variety of possible pitfalls such traditions can create.

The female characters find themselves caught in a variety of social obligations that trap and bind them. Ruksha feels obligated to produce a male heir. Nagma is unable to question or escape her manipulative and domineering father. Both women are subjected to threats of divorce unless they cooperate. Overall, the film is remarkably sympathetic toward women’s position in society.

There is also a racial component to the film. Ajgar, the villain, has dark skin, which is brought up in conjunction with his social status. His conniving and greedy ways seem like the exaggerated and grotesque traits that antisemites attribute to Jews. In the first half of the film, Ajgar is almost comical. He has a badly translated catchphrase that he utters in almost every scene, “I don’t sting, but directly gulp down!” It seems likely that it was meant as comic relief, but once Ajgar is holding a gun to a baby’s head, no comedy can relieve the horror of his actions.

Just as Western humanities has Shakespeare and the Bible as constant touch points, so too India has its two epic poems: the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Both stories are foundational influences throughout Indian culture. Bewaffa Se Waffa bears similarities to both poems, but the character of Ruksha bears a particular resemblance to Sita from The Ramayana.

Sita must endure many trials to win Rama. Her loyalty and optimism are all present in Ruksha. The Ramayana is sometimes described as an example of “bhakti” poetry. Bhakti is usually translated as devotional which is a particularly apt in describingThe Ramayana. The whole story is not only meant as a parable encouraging devotion to the gods, but the story is tightly focused on devotion in general. The three main characters, Rama, Rama’s brother Lakshmana, and Sita, as well as Rama’s faithful servant Hanuman, are all icons of loyalty and devotion. They are used as role models to illustrate what true love and dedication are.

This being said, the one exception is Rama’s love for Sita. His love and trust are not unconditional. After Sita is kidnapped by the team-headed demon Ravanna, she is required to prove that she remained faithful to her marriage vows.

The title “Bewaffa Se Waffa” translates as “Loyal To a Disloyal Man”, which is the title of a song featured in the film. It is sung by Ruksha when she is deserted by Aslam. For someone who was “disloyal”, as well as cold-hearted and cruel, Aslam still gets the girl in the end. This hearkens back to Sita. Both Ruksha and Sita show their piety through steadfast devotion to not only their men, but to what is right, regardless of the emotional anguish involved. Ruksha is kind and open-hearted, no matter who she is with.

The Mahabharata tells us that we ought not be pulled by the fruits of our labor, but instead, we should always do what is right, regardless of the outcome. It’s a complex bit of philosophy that doesn’t fare well out of context, but Rukshar’s unflappable kindness is precisely the kind of behavior it is referring to.

Bewaffa Se Waffa was written, directed, and produced by Saawan Kumar Tak in 1992. Tak is most famous for his film Souten, which he made in 1983. He died in 2022, having made 20 films and wrote music for many more. The music in Bewaffa Se Waffa is nothing special. There are some traditional Indian rhythms, but the songs feel like overproduced blends of Phil Specter’s wall-of-sound style, dated disco synthesizers, and saccharine symphonic music, all recorded with the requisite overdriven distortion present in almost all Bollywood films. I did a little research into why most Bollywood soundtracks are so degraded and found a lot of plausible conjecture, but could not find a definitive answer.

As a film, Bewaffa Se Waffa’soverall quality is inconsistent, but as a Bollywood artifact, it contains a rich well of information. There is a plethora of material to unpack and appreciate, and as a whole, the film’s depiction of women is surprisingly progressive. It may contain many of the common tropes of Bollywood, but it all also contains many ideas I have never seen addressed as seriously in other Bollywood films.

If you enjoyed this article you might also enjoy this -https://filmofileshideout.com/archives/rajamoulis-2022-big-budget-blockbuster-rrr/