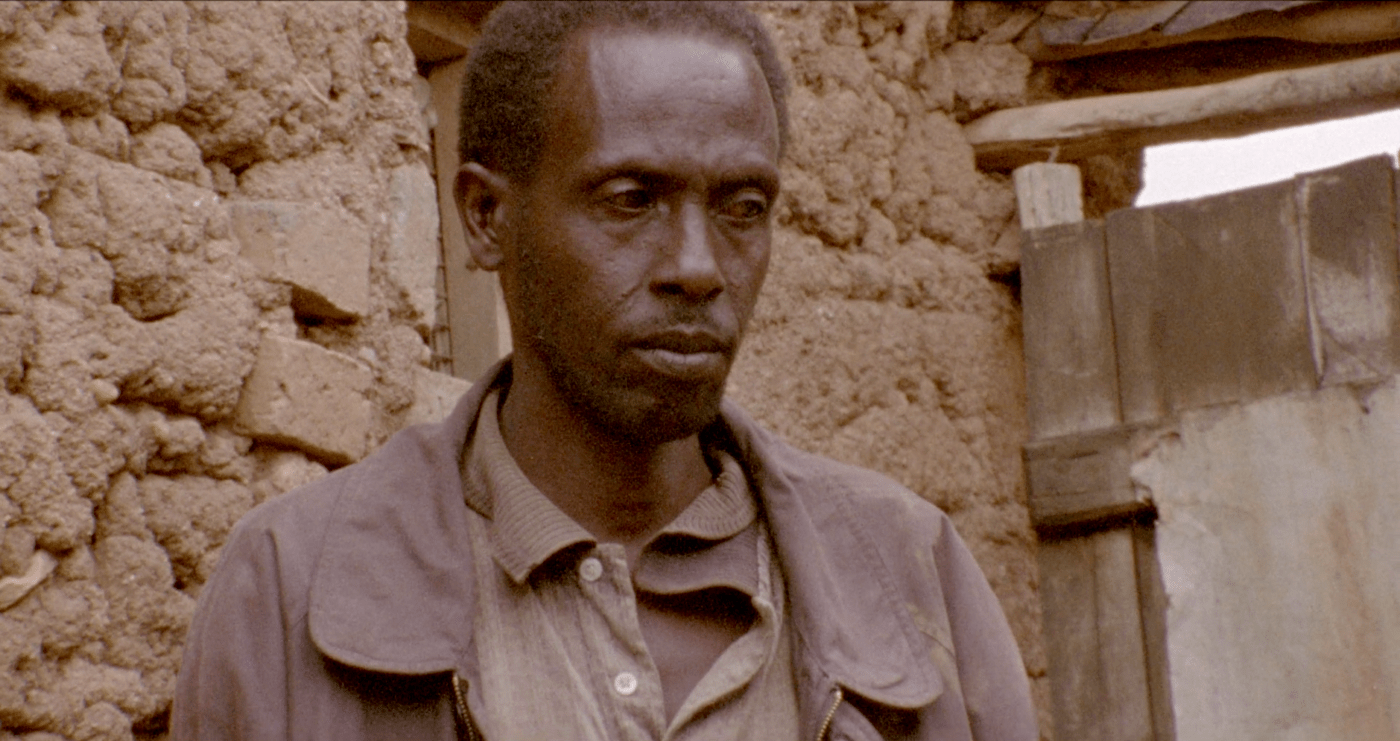

Munyurangabo is a powerful and intense film. The film has nothing but the bare essentials necessary. Its minimalism throws everything into stark relief. The ingredients are two teenage boys, dirt, sky, and a family. There is nothing to hang on to, nothing to cushion you from the drama, just a set of characters dealing with their decisions and each other.

The way the characters talk emphasizes this paucity. None of them speak unless they have something to say and when they say it they relay it in the most direct and blunt way possible. If someone is offended, they say “you offended me.” There is no equivocation, there’s no diplomacy, just a bare relating of what they are thinking or feeling.

The film is about survival. It is about the people who survived the Tutsi holocaust and who must find a way to survive the resulting trauma. It is about how survivors find a way to continue surviving. It is about a way forward for the boys, for the family, and for Rwanda. The film makes no bones about being advocating for unity and against enmity and violence. Without breaking the fourth wall there are several shots where the characters look straight into the camera. The shots are presented in the context of dialogue but we clearly feel the character’s eyes upon us. It’s almost as if they know that they are examples that are being observed. Their challenges are a personalized version of what the country of Rwanda must contend with.

One of the boys is named Munyurangabo. He seems to be a supporting character but it is his conflict that closes the film. He is a Tutsi and the boy who is traveling with him, Ndorunkundiye, is a Hutu. They never speak of this difference and the closeness of their relationship clearly transcends tribal concerns. However, Munyurangabo has convinced Ndorunkundiye, to help him find and kill the man who killed Munyurangabo’s father.

On the way, they stop by Ndorunkundiye’s family home and stay with them for a few days. The drama centers around Ndorunkundiye who has been away from home for three years and has lost touch with his family, his roots, and the values he was raised with. Munyurangabo takes a back seat while this drama unfolds.

There is something of an American Western element to the film. There is the theme of the wanderer who must find his way through an immoral world and eventually find redemption. Rwanda may not look like John Ford’s Utah but Rwanda does have the same exposed earth and dusty vistas. There is that same sense of the simple homesteader trying to carve out a living in a challenging landscape where there is little more to work with than one’s own grit.

Ndorunkundiye’s father is a wonderfully contradictory character. He is the patriarchal keeper of the flame. Ndorunkundiye admires him, fears him, and above all desires his approval. The father works hard on his farm and to keep the honor of his family, but along with this adherence to tradition comes a hatred for the Tutsi which strains the friendship between the two boys.

Munyurangabo provides us with characters pulled by forces and events far larger than themselves. The tenuous and blurred separation between the personal and the political, between historical context and the present, is precisely what makes it difficult to write about enormous eruptions of horror like the genocide of 1994. To speak about it historically from an impartial vantage point is not only impossible but can not convey the depth and breadth of what happened. Smaller stories do not attempt to convey the whole picture but they can connect us more deeply to what happened, even if it is only to a few people.

When considering the slaughter of Tutsis, is it more powerful to explain the statistics, 80,000 were murdered, or is more intense to develop a character and then relay his or her suffering? It need not be a completely exclusive choice, but it is difficult to do both.

Munyurangabo was made in Rwanda in 1997. The director, Lee Isaac Chung, worked almost entirely with local people to supply not only the actors but much of the crew. The film was not only about healing but was itself a means of healing for those who worked on it. The way we experience trauma boils down to the story we construct to bring meaning to the experience. If we are overwhelmed by terror or pain the stories we write, regardless of their truth or falsity, often help in the short term but may end up compounding and perpetuating the trauma in the long run. It is only through rewriting that story that we can find a way forward and perhaps a way to heal.

Munyurangabo is one story among millions generated by the events of 1994. It is a fiction but that doesn’t matter. All stories are fictions in that they construct cause and effect relationships through the myopic lens of our limited perceptions and then molds them into something we can understand and use. In that way, Munyurangabo like all stories is a means to an end, a way of trying to make sense of something that disrupts our understanding of the world and threatens to overwhelm everything. Stories have the power to ground our experiences and allow us to integrate them into our worldview.

The facts of 1994 have no true explanation or ultimate meaning but we desire meaning regardless of whether it exists or not. When faced with pain we insist that it have a cause, someone or something must be at fault. We are so insistent that we will even blame ourselves rather than face the possibility that our suffering was random or meaningless. When the victim blames the victim the trauma only gets deeper.

Munyurangabo is one step in a process of writing and rewriting the events of 1994 in such a way as to allow Rwanda to heal and move forward.

If you liked this article you might also like this -

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/omo-child-a-challenge-for-multiculturalism